Abstract

Modern research of holotropic states (a large special subgroup of

non-ordinary states of consciousness), such as experiential psychotherapy,

clinical and laboratory work with psychedelic substances, field

anthropology, thanatology, and therapy with individuals undergoing

psychospiritual crises ('spiritual emergencies'), has generated a plethora

of extraordinary observations that have undermined some of the most

fundamental assumptions of modern psychiatry, psychology, and

psycho-therapy.

Some of these new findings seriously challenge the most basic philosophical

tenets of Western science concerning the relationship between matter, life,

and consciousness. This paper summarizes the most important major revisions

that would have to be made in our understanding of consciousness and of the

human psyche in health and disease to accommodate these conceptual

challenges:

1. Contrary to academic science, the 'software' of the human psyche is not

limited to postnatal biography and the Freudian individual unconscious. The

individual human psyche includes two important additional dimensions - the

perinatal domain, closely related to the trauma of birth, and the

transpersonal realm, the source of experiences transcending the body-ego -

and is essentially commensurate with all of existence.

2. Emotional and psychosomatic disorders of psychogenic origin cannot be

adequately explained from postnatal traumatic events; they have significant

perinatal and transpersonal roots. For this reason, effective psychotherapy

has to include these transbiographical domains and cannot be limited to the

work on the material from postnatal life.

3. In addition to manipulation of biographical material that is currently

used by various schools of Western psychotherapy, holotropic states offer

powerful experiential healing mechanisms that become available on the

perinatal and transpersonal levels of the psyche, such as reliving of

biological birth and the experience of psychospiritual death and rebirth,

past life experiences, archetypal sequences, episodes of cosmic unity, and

others.

4. Holotropic states, whether spontaneous or induced, mobilize intrinsic

healing forces within the organism. Properly understood and supported, they

can result in emotional and psychosomatic healing, positive personality

transformation, and consciousness evolution. They offer therapeutic

possibilities that are radically different from and superior to the

conventional efforts to rationally understand the dynamics of emotional

disorders and treat them by verbal psychotherapeutic interventions

reflecting the beliefs of various schools of psychotherapy.

5. Spirituality in its genuine form is a legitimate and important dimension

of existence and it is incorrect to discount it as a product of ignorance,

superstition, primitive magical thinking, or pathology. Mystical

experiences should not be seen as indications of mental disease, but as

normal and highly desirable manifestations of the human psyche that have

extraordinary healing and transformative potential.

6. Many of the experiences in non-ordinary states of consciousness

seriously challenge not only the current psychiatric and psychological

theories, but also the basic philosophical assumptions of Western

materialistic science concerning the nature of reality and the relationship

between matter and consciousness. In the light of the new findings,

consciousness is not a product of the neurophysiological processes in the

brain, but a fundamental aspect of existence that is mediated, but not

produced by the brain.

Holotropic Experiences and Their Healing and Heuristic Potential

The source of observations explored in this article has been long-term

systematic study of what academic psychiatry calls 'altered' or

'non-ordinary states of consciousness.' The primary focus of this research

was on experiences that represent a useful source of data about the human

psyche and on those that have a healing, transformative, and evolutionary

potential. For this purpose, the term 'non-ordinary states of

consciousness' is too general; it includes a wide range of conditions that

are not interesting or relevant from this point of view.

Consciousness can be profoundly changed by a variety of pathological

processes -- by cerebral traumas, by intoxications with poisonous

chemicals, by infections, or by degenerative and circulatory processes in

the brain. Such conditions can result in profound mental changes that would

be included in the broad category of 'non-ordinary states of

consciousness'. However, they cause 'trivial deliria' or 'organic

psychoses', states associated with general disorientation, impairment of

intellect, and subsequent amnesia. These conditions are very important

clinically, but are not of great interest for consciousness researchers.

This article summarizes observations focusing on a large and important

subgroup of non-ordinary states of consciousnes for which contemporary

psychiatry does not have a specific term. I have come to the conclusion

that, because of their unique characteristics, they deserve to be

distinguished from the rest and placed into a special category. For this

reason, I coined for them the name holotropic. This composite word

literally means "oriented toward wholeness" or "moving in the direction of

wholeness" (from the Greek holos = whole and trepein = moving toward or in

the direction of something). The full meaning of this term and the

justification for its use will become clear later in this paper. This name

suggests that in our everyday state of consciousness we are fragmented and

identify with only a small fraction of who we really are.

In holotropic states, consciousness is changed qualitatively in a very

profound and fundamental way, but it is not grossly impaired like in

organic psychoses or trivial deliria. We experience invasion of other

dimensions of existence that can be very intense and even overwhelming.

However, at the same time, we typically remain fully oriented and do not

completely lose touch with everyday reality. Holotropic states are

characterized by a specific transformation of consciousness associated with

dramatic perceptual changes in all sensory areas, intense and often unusual

emotions, and profound alterations in the thought processes. They are also

usually accompanied by a variety of intense psychosomatic manifestations

and unconventional forms of behavior.

The content of holotropic states is often spiritual or mystical. We can

experience sequences of psychological death and rebirth and a broad

spectrum of transpersonal phenomena, such as feelings of union and

identification with other people, nature, the universe, and God. We might

uncover what seem to be memories from other incarnations, encounter

powerful archetypal figures, communicate with discarnate beings, and visit

numerous mythological landscapes. Our consciousness might separate from our

body and yet retain its capacity to perceive the immediate environment and

remote locations.

Western psychiatrists are aware of the existence of holotropic experiences

but, because of their narrow conceptual framework limited to postnatal

biography and the Freudian individual unconscious, they have no adequate

explanation for them. They see them as pathological products of the brain,

symptomatic of a serious mental disease, psychosis. This conclusion is not

supported by clinical findings and is highly problematic, to say the least.

Referring to these conditions as 'endogenous psychoses' might sound

impressive to a lay person, but amounts to little more than acknowledgment

of the professionals' ignorance concerning the etiology of these conditions.

It is hard to imagine that and how a pathological process inflicting the

brain could produce the rich and intricate spectrum of holotropic

experiences, involving such phenomena as shattering sequences of

psychospiritual death and rebirth, encounters with archetypal beings,

visits to mythological realms, past life sequences from other cultures, or

visions of flying saucers and alien abduction experiences. In addition,

careful study of the nature of these experiences and the information they

convey directly contradicts such an interpretation. One of the tasks of

this paper is to explore the ontological status of holotropic experiences

and to demonstrate that they are phenomena sui generis - normal

manifestations of the human psyche that have a great healing and heuristic

potential.

Ancient and aboriginal cultures have spent much time and energy developing

powerful mind-altering techniques that can induce holotropic states. These

'technologies of the sacred' combine in different ways chanting, breathing,

drumming, rhythmic dancing, fasting, social and sensory isolation, extreme

physical pain, and other elements (Eliade 1964, Campbell 1984). Many

cultures have used for this purpose botanical materials containing

psychedelic alkaloids (Stafford 1977, Schultes and Hofmann 1979).

The most famous examples of these plants are several varieties of hemp,

'magic' mushrooms, the Mexican cactus peyote, South American and Caribbean

snuffs, the African shrub eboga, and the Amazonian jungle liana

Banisteriopsis caapi, the source of yagé or ayahuasca. Among psychedelic

materials of animal origins are the secretions of the skin of certain toads

and the flesh of the Pacific fish Kyphosus fuscus.

Additional important triggers of holotropic experiences are various forms

of systematic spiritual practice involving meditation, concentration,

breathing, and movement exercises, that are used in different systems of

yoga, Vipassana or Zen Buddhism, Tibetan Vajrayana, Taoism, Christian

mysticism, Sufism, or Cabalah. Other techniques were used in the ancient

mysteries of death and rebirth, such as the Egyptian temple initiations of

Isis and Osiris and the Greek Bacchanalia, rites of Attis and Adonis, and

the Eleusinian mysteries. The specifics of the procedures involved in these

secret rites have remained for the most part unknown, although it is likely

that psychedelic preparations played an important part in them (Wasson,

Hofmann, and Ruck 1978).

Among modern means of inducing holotropic states of consciousness are pure

active principles isolated from psychedelic plants (mescaline, psilocybine,

tryptamine derivatives, harmaline, ibogaine, cannabinols, and others),

substances synthetized in the laboratory (LSD, amphetamine entheogens, and

ketamine) (Shulgin and Shulgin 1991), and powerful experiential forms of

psychotherapy, such as hypnosis, neo-Reichian approaches, primal therapy,

and rebirthing. My wife Christina and I have developed holotropic

breathwork, a powerful method that can facilitate profound holotropic

states by very simple means - conscious breathing, evocative music, and

focused bodywork (Grof 1988).

There also exist very effective laboratory techniques for altering

consciousness. One of these is sensory isolation, which involves

significant reduction of meaningful sensory stimuli. In its extreme form

the individual is deprived of sensory input by submersion in a dark and

soundproof tank filled with water of body temperature (Lilly 1977). Another

well-known laboratory method of changing consciousness is biofeedback,

where the individual is guided by electronic feedback signals into

non-ordinary states of consciousness characterized by preponderance of

certain specific frequencies of brainwaves (Green and Green 1978). We could

also mention here the techniques of sleep and dream deprivation and lucid

dreaming (LaBerge 1985).

It is important to emphasize that episodes of holotropic states of varying

duration can also occur spontaneously, without any specific identifiable

cause, and often against the will of the people involved. Since modern

psychiatry does not differentiate between mystical or spiritual states and

mental diseases, people experiencing these states are often labeled

psychotic, are hospitalized, and receive routine suppressive

psychopharmacological treatment. My wife and I see these states as

psychospiritual crises or 'spiritual emergencies.' We believe that properly

supported and treated, they can result in emotional and psychosomatic

healing, positive personality transformation, and consciousness evolution

(Grof and Grof 1989, 1990).

Ancient and pre-industrial cultures have held holotropic states in high

esteem, practiced them regularly in socially sanctioned contexts, and spent

much time and energy developing safe and effective techniques of inducing

them. These states have been the main vehicle for their ritual and

spiritual life, as a means of direct communication with the archetypal

domains of deities and demons, forces of nature, animal realm, and the

cosmos. Additional uses involved diagnosing and healing diseases,

cultivating intuition and ESP, and obtaining artistic inspiration, as well

as practical purposes, such as locating game and finding lost objects and

people. According to anthropologist Victor Turner, sharing in groups also

contributes to tribal bonding and tends to create a sense of deep

connectedness (communitas).

Western psychiatry and psychology do not see holotropic states (with the

exception of dreams that are not recurrent or frightening) as potential

sources of valuable information about the human psyche and of healing, but

basically as pathological phenomena. Traditional clinicians tend to use

indiscriminately pathological labels and suppressive medication whenever

these states occur spontaneously. Michael Harner, an anthropologist of good

academic standing, who also underwent a shamanic initiation during his

field work in the Amazonian jungle and practices shamanism, suggests that

Western psychiatry is seriously biased in at least two significant ways

(Harner 1980).

It is ethnocentric, which means that it considers its own view of the human

psyche and of reality to be the only correct one and superior to all those

shared by other cultural groups. From this perspective, experiences and

behaviors for which there is no psychoanalytic or behaviorist explanation

are attributed to mental disease. According to Harner, Western psychiatry

is also 'cognicentric' (a more accurate word might be 'pragmacentric'),

meaning that it takes into consideration only experiences and observations

in the ordinary state of consciousness. Psychiatry's disinterest in

holotropic states and disregard for them has resulted in a culturally

insensitive approach and a tendency to pathologize all activities that

cannot be understood in the narrow context of the monistic materialistic

paradigm. This includes the ritual and spiritual life of ancient and

pre-industrial cultures and the entire spiritual history of humanity.

If we study systematically the experiences and observations associated with

holotropic states, it leads inevitably to a radical revision of our basic

ideas about consciousness and about the human psyche and to an entirely new

approach to psychiatry, psychology, and psychotherapy. The changes we would

have to make in our thinking fall into several large categories:

1. New understanding and cartography of the human psyche.

2. The nature and architecture of emotional and psychosomatic disorders.

3. Therapeutic mechanisms and the process of healing.

4. The strategy of psychotherapy and self-exploration.

5. The role of spirituality in human life.

6. The nature of reality.

1. New understanding and cartography of the human psyche.

Traditional academic psychiatry and psychology uses a model of the psyche

that is limited to postnatal biography, and the Freudian individual

unconscious. To account for all the phenomena occurring in holotropic

states, our understanding of the dimensions of the human psyche has to be

drastically expanded. I have myself suggested a cartography or model of the

psyche that contains, in addition to the usual biographical level, two

transbiographical realms: the perinatal domain, related to the trauma of

biological birth; and the transpersonal domain, which accounts for such

phenomena as experiential identification with other people, animals, and

plants, visions of archetypal and mythological beings and realms,

ancestral, racial, and karmic experiences, and identification with the

Universal Mind or the Void (Grof 1975). These are experiences that have

been described throughout ages in the religious, mystical, and occult

literature.

Postnatal Biography and the Individual Unconscious

The biographical level of the psyche does not require much discussion,

since it is well known from official professional literature. As a matter

of fact, it is what traditional psychiatry, psychology, and psychotherapy

are all about. However, there are a few important differences between

exploring this domain through verbal psychotherapy and through approaches

using holotropic states. First, in powerful experiential therapies, one

does not just remember emotionally significant events or reconstruct them

indirectly from dreams, slips of the tongue, or from transference

distortions. One experiences the original emotions, physical sensations,

and even sensory perceptions in full age regression. That means that during

the reliving of an important trauma from infancy or childhood, one actually

has the body image, the naive perception of the world, sensations, and the

emotions corresponding to the age he or she was at that time.

The second difference between the work on the biographical material in

holotropic states, as compared with verbal psychotherapies, is that in the

former, beside confronting the usual psychotraumas, people often have to

relive and integrate traumas that were primarily of a physical nature. Many

people have to process experiences of near drowning, operations, accidents,

and children's diseases, particularly those that were associated with

suffocation, such as diphtheria, whooping cough, or aspiration of a foreign

object.

This material emerges quite spontaneously and without any programing. As it

surfaces, people realize that these physical traumas have actually played a

significant role in the psychogenesis of their emotional and psychosomatic

problems, such as asthma, migraine headaches, a variety of psychosomatic

pains, phobias, sadomasochistic tendencies, or depression and suicidal

tendencies. The reliving of such traumatic memories and their integration

can then have very far-reaching therapeutic consequences. This contrasts

sharply with the attitudes of academic psychiatry and psychology which do

not recognize the direct psychotraumatic impact of physical insults.

Another new information about the biographical-recollective level of the

psyche that emerged from my psychedelic and holotropic research was the

discovery that emotionally relevant memories are not stored in the

unconscious as a mosaic of isolated imprints, but in the form of complex

dynamic constellations. I coined for them the name COEX systems, which is

short for 'systems of condensed experience.' A COEX system consists of

emotionally charged memories from different periods of our life that

resemble each other in the quality of emotion or physical sensation that

they share. Each COEX has a basic theme that permeates all its layers and

represents their common denominator. The individual layers then contain

variations on this basic theme that occurred at different periods of the

person's life.

The nature of the central theme varies considerably from one COEX to

another. The layers of a particular system can, for example contain all the

major memories of humiliating, degrading, and shaming experiences that have

damaged our self-esteem. In another COEX system, the common denominator

can be anxiety experienced in various shocking and terrifying situations or

claustrophobic and suffocating feelings evoked by oppressive and confining

circumstances. Rejection and emotional deprivation damaging our ability to

trust men, women, or people in general, is another common motif.

Situations that have generated in us profound feelings of guilt and a sense

of failure, events that have left us with a conviction that sex is

dangerous or disgusting, and encounters with indiscriminate aggression and

violence can be added to the above list as characteristic examples.

Particularly important are COEX systems that contain memories of encounters

with situations endangering life, health, and integrity of the body.

When I first described the COEX systems in the early stages of my

psychedelic research, I thought that they governed the dynamics of the

biographical level of the unconscious. As my experience with holotropic

states became richer and more extensive, I realized that the roots of the

COEX systems reach much deeper. Each of the COEX constellations seems to be

superimposed over and anchored in a particular aspect of the trauma of

birth. In addition, a typical COEX system reaches even further and has its

deepest roots in various forms of transpersonal phenomena, such as past

life experiences, Jungian archetypes, conscious identification with various

animals, and others. At present, I see the COEX systems as general

organizing principles of the human psyche. The concept of COEX systems

resembles to some extent Jung's ideas about psychological complexes (Jung

1960) and Hanskarl Leuner's transphenomenal dynamic systems Leuner 1962),

but has many features that differentiate it from both of these concepts.

The COEX systems play an important role in our psychological life. They can

influence the way we perceive ourselves, other people, and the world and

how we feel about them. They are the dynamic forces behind our emotional

and psychosomatic symptoms, difficulties in relationships with other

people, and irrational behavior. There exists a dynamic interplay between

the COEX systems and the external world. External events in our life can

specifically activate corresponding COEX systems and, conversely, active

COEX systems can make us perceive and behave in such a way that we recreate

their core themes in our present life (Grof 1975).

Before continuing our discussion of the new extended cartography of the

human psyche, it is important to briefly mention a very important and

extraordinary characteristic of holotropic states that played an important

role in charting the experiential territories of the psyche and that also

is invaluable for the process of psychotherapy. Holotropic states tend to

engage something like an 'inner radar,' that automatically brings into

consciousnes the contents from the unconscious that have the strongest

emotional charge and are most psychodynamically relevant at the time. This

represents a great advantage in comparison with verbal psychotherapy, where

the client presents a broad array of information of various kind and the

therapist has to decide what is important, what is irrelevant, and where

the client is blocking.

Since there is no general agreement about basic theoretical issues among

different schools, such assessments will always be idiosyncratic. They will

reflect the perspectives of the therapist's school, as well as his or her

personal views. The holotropic states save the therapist such difficult

decisions and eliminate much of the personal and professional bias of the

verbal approaches. This automatic selection of relevant material by the

patient's psyche also spontaneously guides the process of self-exploration

beyond the biographical level and directs it to the perinatal and

transpersonal levels of the psyche. These are transbiographical domains not

recognized and acknowledged in academic psychiatry and psychology.

The Perinatal Level of the Psyche

When our process of deep experiential self-exploration moves beyond the

level of memories from childhood and infancy and reaches back to birth, we

start encountering emotions and physical sensations of extreme intensity,

often surpassing anything we previously considered humanly possible. At

this point, the experiences become a strange mixture of the themes of birth

and death. They involve a sense of a severe, life-threatening confinement

and a desperate and determined struggle to free ourselves and survive. This

intimate relationship between birth and death on the perinatal level

reflects the fact that birth is a potentially life - threatening event. The

child and the mother can actually lose their lives during this process and

children might be born severely blue from asphyxiation, or even dead and in

need of resuscitation.

The reliving of various aspects of biological birth can be very authentic

and convincing and often replays this process in photographic detail. This

can occur even in people who have no intellectual knowledge about their

birth and lack elementary obstetric information. We can, for example,

discover through direct experience that we had a breech birth, that a

forceps was used during our delivery, or that we were born with the

umbilical cord twisted around the neck. We can feel the anxiety, biological

fury, physical pain, and suffocation associated with this terrifying event

and even accurately recognize the type of anesthesia used when we were

born. This is often accompanied by various postures and movements of the

head and body that accurately recreate the mechanics of a particular type

of delivery. All these details can be confirmed if good birth records or

reliable personal witnesses are available.

The strong representation of birth and death in our psyche and the close

association between them might surprise traditional psychologists and

psychiatrists, but is actually logical and easily understandable. The

delivery brutally terminates the intrauterine existence of the fetus. He or

she 'dies' as an aquatic organism and is born as an air-breathing,

physiologically, and even anatomically, different form of life. And the

passage through the birth canal is itself a difficult and potentially life

- threatening situation.

It is not so easy to understand, why the perinatal dynamics also regularly

includes a sexual component. And yet, when we are reliving the final stages

of birth in the role of the fetus, this is typically associated with an

unusually strong sexual arousal. The same is true for delivering women, who

can experience a mixture of fear of death and intense sexual excitement.

This connection seems strange and puzzling, particularly as far as the

fetus is concerned, and certainly deserves a few words of explanation.

There seems to be a mechanism in the human organism that transforms extreme

suffering, especially when it is associated with suffocation, into a

particular form of sexual arousal. This experiential connection can be

observed in a variety of situations other than birth. People who had tried

to hang themselves and were rescued in the last moment typically describe

that, at the height of suffocation, they felt an almost unbearable sexual

arousal. It is known that males executed by hanging typically have an

erection and even ejaculate.

The literature on torture and brainwashing describes that inhuman physical

suffering often triggers states of sexual ecstasy. In the sects of

flagellants, who regularly engage in self-inflicted torture, and in

religious martyrs, subjected to unimaginable torments, extreme physical

pain at a certain point changes into sexual arousal and eventually results

in ecstatic rapture and transcendental experiences. In a less extreme form,

this mechanism operates in various sadomasochistic practices that include

strangulation and choking.

The experiential spectrum of the perinatal domain of the unconscious is not

limited to emotions and physical sensations that can be derived from the

biological processes involved in childbirth. It also involves rich symbolic

imagery that is drawn from the transpersonal realms. The perinatal domain

is an important interface between the biographical and the transpersonal

levels of the psyche. It represents a gateway to the to historical and

archetypal aspects of the collective unconscious in the Jungian sense.

Since the specific symbolism of these experiences has its origin in the

collective unconscious, and not in the individual memory banks, it can come

from any geographical and historical context, as well as any spiritual

tradition of the world, quite independently from our racial, cultural,

educational, or religious background.

Identification with the infant facing the ordeal of the passage through the

birth canal seems to provide access to experiences of people from other

times and cultures, of various animals, and even mythological figures. It

is as if by connecting with the experience of the fetus struggling to be

born, one reaches an intimate, almost mystical, connection with the

consciousness of the human species and with other sentient beings who are

or have been in a similar difficult predicament.

Experiential confrontation with birth and death seems to result

automatically in a spiritual opening and discovery of the mystical

dimensions of the psyche and of existence. It does not seem to make a

difference whether this encounter with birth and death occurs in actual

life situations, such as in delivering women and in the context of

near-death experiences, or is purely symbolic. Powerful perinatal sequences

in psychedelic and holotropic sessions or in the course of spontaneous

psychospiritual crises ('spiritual emergencies') seem to have the same

effect.

Biological birth has three distinct stages. In the first one, the fetus is

periodically constricted by uterine contractions without having any chance

of escaping this situation, since the cervix is firmly closed. Continued

contractions pull the cervix over the fetus' head until it is sufficiently

dilated to allow the passage through the birth canal. Full dilation of the

cervix and descent of the head into the pelvis mark the transition from the

first to the second stage of delivery that is characterized by gradual

difficult propulsion through the birth pathways. And finally, in the third

stage, the newborn emerges from the birth canal and, after the umbilical

cord is cut, he or she becomes an anatomically independent organism.

At each of these stages, the baby experiences a specific and typical set of

intense emotions and physical sensations. These experiences leave deep

unconscious imprints in the psyche that later in life play an important

role in the life of the individual. Reinforced by emotionally important

experiences from infancy and childhood, the birth memories can shape the

perception of the world, profoundly influence everyday behavior, and

contribute to the development of various emotional and psychosomatic

disorders.

In holotropic states, this unconscious material can surface and be fully

experienced. When our process of deep self-exploration takes us back to

birth, we discover that reliving each stage of delivery is associated with

a distinct experiential pattern, characterized by a specific combination of

emotions, physical feelings, and symbolic images. I refer to these patterns

of experience as basic perinatal matrices (BPMs).

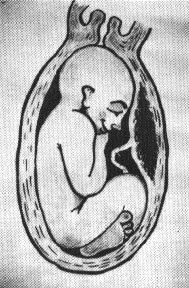

The first perinatal matrix (BPM I.) is related to the intrauterine

experience immediately preceding birth and the remaining three matrices

(BPM II. - BPM IV.) to the three clinical stages of delivery described

above. Besides containing elements that represent a replay of the original

situation of the fetus at a particular stage of birth, the basic perinatal

matrices also include various natural, historical, and mythological scenes

with similar experiential qualities drawn from the transpersonal realms.

The connections between the experiences of the consecutive stages of

biological birth and various symbolic images associated with them are very

specific and consistent. The reason why they emerge together is not

understandable in terms of conventional logic. However, that does not mean

that these associations are arbitrary and random. They have their own deep

order that can best be described as 'experiential logic'. What this means

is that the connection between the experiences characteristic for various

stages of birth and the concomitant symbolic themes are not based on some

formal external similarity, but on the fact that they share the same

emotional feelings and physical sensations.

| | |

First Perinatal Matrix (BPM I).

While experiencing the episodes of undisturbed embryonal existence (BPM

I.), we often encounter images of vast regions with no boundaries or

limits. Sometimes we identify with galaxies, interstellar space, or the

entire cosmos, other times we have the experience of floating in the ocean

or of becoming various aquatic animals, such as fish, dolphins, or whales.

The undisturbed intrauterine experience can also open into visions of

nature - safe, beautiful, and unconditionally nourishing, like a good womb

(Mother Nature). We can see luscious orchards, fields of ripe corn,

agricultural terraces in the Andes, or unspoiled Polynesian islands. The

experience of the good womb can also provide selective access to the

archetypal domain of the collective unconscious and open into images of

paradises or heavens as they are described in the mythologies of different

cultures.

|

|---|

When we are reliving episodes of intrauterine disturbances, or 'bad womb'

experiences, we have a sense of dark and ominous threat and we often feel

that we are being poisoned. We might see images that portray polluted

waters and toxic dumps. This reflects the fact that many prenatal

disturbances are caused by toxic changes in the body of the pregnant

mother. The experience of the toxic womb can be associated with visions of

frightening demonic figures from the archetypal realms of the collective

unconscious. Reliving of more violent interferences during prenatal

existence, such as an imminent miscarriage or attempted abortion, is

usually connected with a sense of universal threat or with bloody

apocalyptic visions of the end of the world.

|

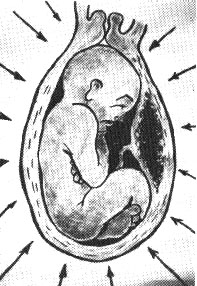

| | Second Basic Perinatal Matrix (BPM II).

When the experiential regression reaches the memory of the onset of

biological birth, we typically feel that we are being sucked into a

gigantic whirlpool or swallowed by some mythical beast. We might also

experience that the entire world or even cosmos is being engulfed. This can

be associated with images of devouring or entangling archetypal monsters,

such as leviathans, dragons, giant snakes, tarantulas, and octopuses. The

sense of overwhelming vital threat can lead to intense anxiety and general

mistrust bordering on paranoia. We can also experience a descent into the

depths of the underworld, the realm of death, or hell. As mythologist

Joseph Campbell so eloquently described, this is a universal motif in the

mythologies of the hero's journey (Campbell 1968).

|

|---|

Reliving the fully developed first stage of biological birth when the

uterus is contracting, but the cervix is not yet open (BPM II.), is one of

the worst experiences a human being can have. We feel caught in a monstrous

claustrophobic nightmare, are suffering agonizing emotional and physical

pain, and have a sense of utter helplessness and hopelessness. Our feelings

of loneliness, guilt, absurdity of life, and existential despair can reach

metaphysical proportions. We lose connection with linear time and are

convinced that this situation will never end and that there is absolutely

no way out. There is no doubt in our mind that what is happening to us is

what the religions refer to as Hell - unbearable emotional and physical

torment without any hope for redemption. This can actually be accompanied

by archetypal images of devils and infernal landscapes from different

cultures.

When we are facing the dismal situation of no exit in the clutches of

uterine contractions, we can experientially connect with sequences from

the collective unconscious that involve people, animals, and even

mythological beings who are in a similar painful and hopeless predicament.

We identify with prisoners in dungeons, inmates of concentration camps or

insane asylums, and with animals caught in traps. We might experience the

intolerable tortures of sinners in hell or of Sisyphus rolling his boulder

up the mountain in the deepest pit of Hades.

Our pain can become the agony of Christ asking God why He has abandoned

him. It seems to us that we are facing the prospect of eternal damnation.

This state of darkness and abysmal despair is known from the spiritual

literature as the Dark Night of the Soul. From a broader perspective, in

spite of the feelings of utter hopelessness that it entails, this state is

an important stage of spiritual opening. If it is experienced to its full

depth, it can have an immensely purging and liberating effect on those who

experience it.

|

| | Third Basic Perinatal Matrix (BPM III).

The experience of the second stage of birth, the propulsion through the

birth canal after the cervix opens and the head descends (BPM III.), is

unusually rich and dynamic. Facing the clashing energies and hydraulic

pressures involved in the delivery, we are flooded with images from the

collective unconscious portraying sequences of titanic battles and scenes

of bloody violence and torture. It is also during this phase that we are

confronted with sexual impulses and energies of problematic nature and

unusual intensity.

|

|---|

It has already been described earlier that sexual arousal is an important

part of the experience of birth. This places our first encounter with

sexuality into a very precarious context, into a situation where our life

is threatened, where we are suffering pain as well as inflicting pain, and

where we are unable to breathe. At the same time, we are experiencing a

mixture of vital anxiety and primitive biological fury, the latter being an

understandable reaction of the fetus to this painful and life - threatening

experience. In the final stages of birth, we can also encounter various

forms of biological material - blood, mucus, urine, and even feces.

Because of these problematic connections, the experiences and images that

we encounter in this phase typically present sex in a grossly distorted

form. The strange mixture of sexual arousal with physical pain, aggression,

vital anxiety, and biological material leads to sequences that are

pornographic, aberrant, sadomasochistic, scatological, or even satanic. We

can be overwhelmed by dramatic scenes of sexual abuse, perversions, rapes,

and erotically motivated murders.

On occasion, these experiences can take the form of participation in

rituals featuring witches and satanists. This seems to be related to the

fact that reliving this stage of birth involves the same strange

combination of emotions, sensations, and elements that characterizes the

archetypal scenes of the Black Mass and of the Witches' Sabbath (Walpurgi's

Night). It is a mixture of sexual arousal, panic anxiety, aggression, vital

threat, pain, sacrifice, and encounter with ordinarily repulsive biological

materials. This peculiar experiential amalgam is associated with a sense of

sacredness or numinosity which reflects the fact that all this is unfolding

in close proximity to a spiritual opening.

This stage of the birth process can also be associated with countless

images from the collective unconscious portraying scenes of murderous

aggression, such as vicious battles, bloody revolutions, gory massacres,

and genocide. In all the violent and sexual scenes that we encounter at

this stage, we alternate between the role of the perpetrator and that of

the victim. This is the time of a major encounter with the dark side of our

personality, Jung's Shadow.

As this perinatal phase culminates and approaches resolution, many people

envision Jesus, the Way of the Cross, and crucifixion, or even actually

experience full identification with Jesus' suffering. The archetypal domain

of the collective unconscious contributes to this phase heroic mythological

figures and deities representing death and rebirth, such as the Egyptian

god Osiris, the Greek deities Dionysus and Persephone, or the Sumerian

goddess Inanna.

|

| | Fourth Perinatal Matrix (BPM IV).

The reliving of the third stage of the birth process, of the actual

emergence into the world (BPM IV.), is typically initiated by the motif of

fire. We can have the feeling that our body is consumed by searing heat,

have visions of burning cities and forests, or identify with victims of

immolation. The archetypal versions of this fire can take the form of the

cleansing flames of Purgatory or of the legendary bird Phoenix, dying in

the heat of his burning nest and emerging from the ashes reborn and

rejuvenated. The purifying fire seems to destroy in us whatever is

corrupted and prepare us for spiritual rebirth. When we are reliving the

actual moment of birth, we experience it as complete annihilation and

subsequent rebirth and resurrection.

|

|---|

To understand why we experience the reliving of biological birth as death

and rebirth, one has to realize that what happens to us is much more than

just a replay of the original event of childbirth. During the delivery, we

are completely confined in the birth canal and have no way of expressing

the extreme emotions and sensations involved. Our memory of this event thus

remains psychologically undigested and unassimilated. Much of our later

self - definition and our attitudes toward the world are heavily

contaminated by this constant deep reminder of the vulnerability,

inadequacy, and weakness that we experienced at birth. In a sense, we were

born anatomically but have not really caught up emotionally with the fact

that the emergency and danger are over.

The 'dying' and the agony during the struggle for rebirth reflect the

actual pain and vital threat of the biological birth process. However, the

ego death that immediately precedes rebirth is the death of our old

concepts of who we are and what the world is like, which were forged by the

traumatic imprint of birth. As we are purging these old programs from our

psyche and body by letting them emerge into consciousness, we are reducing

their energetic charge and curtail their destructive influence on our life.

From a larger perspective, this process is actually very healing and

transforming. And yet, as we are nearing its final resolution, we might

paradoxically feel that, as the old imprints are leaving our system, we are

dying with them. Sometimes, we not only experience the sense of personal

annihilation, but also the destruction of the world as we know it.

While only a small step separates us from the experience of radical

liberation, we have a sense of all-pervading anxiety and impending

catastrophe of enormous proportions. The impression of imminent doom can be

very convincing and overwhelming. The predominant feeling is that we are

losing all that we know and that we are. At the same time, we have no idea

what is on the other side, or even if there is anything there at all. This

fear is the reason that at this stage many people desperately resist the

process if they can. As a result, they can remain psychologically stuck in

this problematic territory for an indefinite period of time.

The encounter with the ego death is a stage of the spiritual journey when

we might need much encouragement and psychological support. When we succeed

in overcoming the metaphysical fear associated with this important juncture

and decide to let things happen, we experience total annihilation on all

imaginable levels. It involves physical destruction, emotional disaster,

intellectual and philosophical defeat, ultimate moral failure, and even

spiritual damnation. During this experience, all reference points,

everything that is important and meaningful in our life, seems to be

mercilessly destroyed.

Immediately following the experience of total annihilation - 'hitting

cosmic bottom'- we are overwhelmed by visions of light that has a

supernatural radiance and beauty and is usually perceived as sacred. This

divine epiphany can be associated with displays of beautiful rainbows,

diaphanous peacock designs, and visions of celestial realms with angelic

beings or deities appearing in light. This is also the time when we can

experience a profound encounter with the archetypal figure of the Great

Mother Goddess or one of her many culture - bound forms.

The experience of psychospiritual death and rebirth is a major step in the

direction of the weakening of our identification with the body-ego, or the

'skin-encapsulated ego,' as the British-American writer and philosopher

Alan Watts called it, and reconnecting with the transcendental domain. We

feel redeemed, liberated, and blessed and have a new awareness of our

divine nature and cosmic status. We also typically experience a strong

surge of positive emotions toward ourselves, other people, nature, God, and

existence in general. We are filled with optimism and have a sense of

emotional and physical well - being.

It is important to emphasize that this kind of healing and life - changing

experience occurs when the final stages of biological birth had a more or

less natural course. If the delivery was very debilitating or confounded

by heavy anesthesia, the experience of rebirth does not have the quality of

triumphant emergence into light. It is more like awakening and recovering

from a hangover with dizziness, nausea, and clouded consciousness. Much

additional psychological work might be needed to work through these

additional issues and the positive results are much less striking.

The perinatal domain of the psyche represents an experiential crossroad of

critical importance. It is not only the meeting point of three absolutely

crucial aspects of human biological existence - birth, sex, and death - but

also the dividing line between life and death, the individual and the

species, and the individual human psyche and the universal spirit. Full

conscious experience of the contents of this domain of the psyche with good

subsequent integration can have far - reaching consequences and lead to

spiritual opening and deep personal transformation.

The Transpersonal Domain of the Psyche

The second major domain that has to be added to mainstream psychiatry's

cartography of the human psyche when we work with holotropic states is now

known under the name transpersonal, meaning literally "beyond the personal"

or "transcending the personal". The experiences that originate on this

level involve transcendence of the usual boundaries of the individual (his

or her body and ego) and of the limitations of three-dimensional space and

linear time that restrict our perception of the world in the ordinary state

of consciousness. Transpersonal experiences are best defined by contrasting

them with the everyday experience of ourselves and the world - how we have

to experience ourselves and the environment to pass for 'normal' according

to the standards of our culture and of contemporary psychiatry (Grof 1975,

1988).

In the ordinary or "normal" state of consciousness, we experience ourselves

as Newtonian objects existing within the boundaries of our skin. As I

mentioned earlier, Alan Watts referred to this experience of oneself as

identifying with the "skin-encapsulated ego". Our perception of the

environment is restricted by the physiological limitations of our sensory

organs and by physical characteristics of the environment.

We cannot see objects we are separated from by a solid wall, ships that are

beyond the horizon, or the other side of the moon. If we are in Prague, we

cannot hear what our friends are talking about in San Francisco. We cannot

feel the softness of the lambskin unless the surface of our body is in

direct contact with it. In addition, we can experience vividly and with all

our senses only the events that are happening in the present moment. We can

recall the past and anticipate future events or fantasize about them;

however, these are very different experiences from an immediate and direct

experience of the present moment. In transpersonal states of consciousness,

however, none of these limitations are absolute; any of them can be

transcended.

Transpersonal experiences can be divided into three large categories. The

first of these involves primarily transcendence of the usual spatial

bariers, or the limitations of the 'skin-encapsulated ego.' Here belong

experiences of merging with another person into a state that can be called

'dual unity,' assuming the identity of another person, identifying with the

consciousness of an entire group of people (e.g. all mothers of the world,

the entire population of India, or all the inmates of concentration camps),

or even experiencing an extension of consciousness that seems to encompass

all of humanity. Experiences of this kind have been repeatedly described in

the spiritual literature of the world.

In a similar way, one can transcend the limits of the specifically human

experience and identify with the consciousness of various animals, plants,

or even a form of consciousness that seems to be associated with inorganic

objects and processes. In the extremes, it is possible to experience

consciousness of the entire biosphere, of our planet, or the entire

material universe. Incredible and absurd as it might seem to a Westerner

committed to monistic materialism, these experiences suggest that

everything we can experience in our everyday state of consciousness as an

object, has in the non-ordinary states of consciousness a corresponding

subjective representation. It is as if everything in the universe has its

objective and subjective aspect, the way it is described in the great

spiritual philosophies of the East (e.g. in Hinduism all that exists is

seen as a manifestation of Brahman, or in Taoism as a transformation of the

Tao).

The second category of transpersonal experiences is characterized primarily

by overcoming of temporal rather than spatial boundaries, by transcendence

of linear time. We have already talked about the possibility of vivid

reliving of important memories from infancy and of the trauma of birth.

This historical regression can continue farther and involve authentic fetal

and embryonal memories from different periods of intrauterine life. It is

not even unusual to experience, on the level of cellular consciousness,

full identification with the sperm and the ovum at the time of conception.

But the historical regression does not stop here and it is possible to

have experiences from the lives of one's human or animal ancestors, or even

those that seem to be coming from the racial and collective unconscious as

described by C. G. Jung (Jung 1956, 1959). Quite frequently, the

experiences that seem to be happening in other cultures and historical

periods are associated with a sense of personal remembering; people then

talk about reliving of memories from past lives, from previous incarnations.

In the transpersonal experiences described so far, the content reflects

various phenomena existing in spacetime. They involve elements of the

everyday familiar reality - other people, animals, plants, materials, and

events from the past. What is surprising here is not the content of these

experiences, but the fact that we can witness or fully identify with

something that is not ordinarily accessible to our experience. We know that

there are pregnant whales in the world, but we should not be able to have

an authentic experience of being one. The fact that there once was the

French revolution is readily acceptable, but we should not be able to have

a vivid experience of being there and lying wounded on the barricades of

Paris. We know that there are many things happening in the world in places

where we are not present, but it is usually considered impossible to

experience something that is happening in remote locations (without the

mediation of the television and a satelite). We may also be surprised to

find consciousness associated with lower animals, plants, and with

inorganic nature.

However, the third category of transpersonal experiences is even stranger

than the former two. Here consciousness seems to extend into realms and

dimensions that the Western industrial culture does not consider to be

'real.' Here belong numerous visions of archetypal beings and mythological

landscapes, encounters or even identification with deities and demons of

various cultures, and communication with discarnate beings, spirit guides,

suprahuman entities, extraterrestrials, and inhabitants of parallel

universes.

In its farthest reaches, individual consciousness can identify with Cosmic

Consciousness or the Universal Mind known under many different names -

Brahman, Buddha, the Cosmic Christ, Keter, Allah, the Tao, the Great

Spirit, and many others. The ultimate of all experiences appears to be

identification with the Supracosmic and Metacosmic Void, the mysterious and

primordial emptiness and nothingness that is conscious of itself and is the

ultimate cradle of all existence. It has no concrete content, yet it seems

to contain all there is in a germinal and potential form.

Transpersonal experiences have many strange characteristics that shatter

the most fundamental metaphysical assumptions of the Newtonian-Cartesian

paradigm and of the materialistic world view. Researchers who have studied

and/or personally experienced these fascinating phenomena realize that the

attempts of mainstream science to dismiss them as irrelevant products of

human fantasy and imagination or as hallucinations - erratic products of

pathological processes in the brain - are naive and inadequate. Any

unbiased study of the transpersonal domain of the psyche has to come to the

conclusion that these observations represent a critical challenge not only

for psychiatry and psychology, but for the entire philosophy of Western

science.

Although transpersonal experiences occur in the process of deep individual

self-exploration, it is not possible to interpret them simply as

intrapsychic phenomena in the conventional sense. On the one hand, they

appear on the same experiential continuum as the biographical and perinatal

experiences and are thus coming from within the individual psyche. On the

other hand, they seem to be able to tap directly, without the mediation of

the senses, sources of information that are clearly far beyond the

conventional reach of the individual. Somewhere on the perinatal level of

the psyche, a strange Moebius-like flip seems to occur and what was up to

that point deep intrapsychic probing becomes experiencing of the universe

at large through extrasensory means.

These observations indicate that we can obtain information about the

universe in two radically different ways: Besides the conventional

possibility of learning through sensory perception and analysis and

synthesis of the data, we can also find out about various aspects of the

world by direct identification with them in a holotropic state of

consciousness. Each of us thus appears to be a microcosm containing in a

holographic way the information about the macrocosm. In the mystical

traditions, this was expressed by such phrases as: "as above so below" or

"as without, so within."

The reports of subjects who have experienced episodes of embryonal

existence, the moment of conception, and elements of cellular, tissue, and

organ consciousness abound in medically accurate insights into the

anatomical, physiological, and biochemical aspects of the processes

involved. Similarly, ancestral, racial and collective memories and past

incarnation experiences provide quite frequently very specific details

about architecture, costumes, weapons, art forms, social structure, and

religious and ritual practices of the cultures and historical periods

involved, or even about concrete historical events.

People who experienced phylogenetic experiences or identification with

existing life forms not only found them unusually authentic and convincing,

but often acquired in the process extraordinary insights concerning animal

psychology, ethology, specific habits, or unusual reproductive cycles. In

some instances, this was accompanied by archaic muscular innervations not

characteristic for humans, or even such complex behaviors as enactment of a

courtship dance.

The philosophical challenge associated with the already described

observations, as formidable as it is all by itself, is further augmented

by the fact that the transpersonal experiences correctly reflecting the

material world often appear on the same continuum as and intimately

interwoven with others that contain elements which the Western industrial

world does not consider to be real. Here belong, for example, experiences

involving deities and demons from various cultures, mythological realms

such as heavens and paradises, and legendary or fairy-tale sequences.

For example, one can have an experience of Shiva's heaven, of the paradise

of the Aztec raingod Tlaloc, of the Sumerian underworld, or of one of the

Buddhist hot hells. It is also possible to experience oneself as Jesus on

the cross, have a shattering encounter with the Hindu goddess Kali, or

identify with the dancing Shiva. Even these episodes can impart accurate

new information about religious symbolism and mythical motifs that were

previously unknown to the person involved. Observations of this kind

confirm C. G. Jung's idea that, besides the Freudian individual

unconscious, we can also gain access to the collective unconscious that

contains the cultural heritage of all humanity (Jung 1959).

The existence and nature of transpersonal experiences violates some of the

most basic assumptions of mechanistic science. They imply such seemingly

absurd notions as relativity and arbitrary nature of all physical

boundaries, non-local connections in the universe, communication through

unknown means and channels, memory without a material substrate,

non-linearity of time, or consciousness associated with all living

organisms, and even inorganic matter. Many transpersonal experiences

involve events from the microcosm and the macrocosm, realms that cannot

normally be reached by unaided human senses, or from historical periods

that precede the origin of the solar system, formation of planet earth,

appearance of living organisms, development of the nervous system, and

emergence of homo sapiens.

The research of holotropic states thus reveals a baffling paradox

concerning the nature of human beings. It clearly shows that, in a

mysterious and yet unexplained way, each of us contains the information

about the entire universe and all of existence, has potential experiential

access to all of its parts, and in a sense is the whole cosmic network, as

much as he or she is just an infinitesimal part of it, a separate and

insignificant biological entity. The new cartography reflects this fact and

portrays the individual human psyche as being essentially commensurate with

the entire cosmos and the totality of existence. As absurd and implausible

as this idea might seem to a traditionally trained scientist and to our

commonsense, it can be relatively easily reconciled with new revolutionary

developments in various scientific disciplines usually referred to as the

new or emerging paradigm (Bohm 1980, Sheldrake 1981, Laszlo 1994).

The expanded cartography outlined above is of critical importance for any

serious approach to such phenomena as shamanism, rites of passage,

mysticism, religion, mythology, parapsychology, near-death experiences, and

psychedelic states. This new model of the psyche is not just a matter of

academic interest. As we will see in the following sections of this

article, it has deep and revolutionary implications for the understanding

of emotional and psychosomatic disorders, including psychoses, and offers

exciting new perspectives for therapy.

2. The nature and architecture of emotional and psychosomatic disorders.

Traditional psychiatry uses for the explanations of various disorders that

do not have an organic basis ('psychogenic psychopathology') explanatory

models that are limited to postnatal biography and the Freudian individual

unconscious. They emphasize such factors as traumatic influences in

infancy, childhood, and later life, pathogenic potential of psychological

conflict, the importance of family dynamics and interpersonal

relationships, and the impact of social environment.

The observations from the study of holotropic states of consciousness show

that emotional and psychosomatic disorders, including many states currently

diagnosed as psychotic, cannot be adequately understood from difficulties

in postnatal development. According to the new insights, these conditions

have a multilevel, multidimensional structure with important additional

roots on the perinatal level (trauma of birth) and in the transpersonal

domain (ancestral, racial, and collective memories, karmic experiences, and

archetypal dynamics). Bringing these elements into consideration provides a

radically new, much fuller and complete picture of 'psychopathology.'

Recognition of perinatal and transpersonal roots of emotional disorders

does not imply that the postnatal biographical factors described by

psychoanalysis are irrelevant for their development. The events in infancy

and childhood certainly continue to play an important role in the overall

picture. However, instead of representing the sources of these disorders,

they become important determinants for the emergence of psychological

material from deeper levels of the unconscious.

The unconscious record of the experiences associated with birth represents

a universal pool of difficult emotions and physical sensations that

constitute a potential source for various forms of 'psychopathology.'

Whether manifest symptoms and syndromes actually develop and which form

they take then depends on the reinforcing influence of traumatic events in

postnatal history or, conversely, on the mitigating effect of various

biographical factors. In addition, the emotional and psychosomatic

disorders can be co-determined by various transpersonal factors, such as

karmic, archetypal, or phylogenetic elements. They are thus the result of

a complicated interplay between biographical, perinatal, and transpersonal

factors.

Thus, for example, a person suffering from psychogenic asthma can trace

this disorder to a situation of near drowning at the age of seven, memory

of being choked in childhood by an older brother, an episode of whooping

cough in infancy, suffocation during birth, and past life experiences

involving strangling and hanging. Similarly, the material underlying

claustrophobia can include childhood memories of being repeatedly locked in

a closet or cellar in childhood, a history of swaddling, difficult birth,

and past life episodes of incarceration in a medieval dungeon and a Nazi

concentration camp, and so on.

The scope of this paper does not allow me to demonstrate how profoundly the

new observations change our understanding of a broad spectrum of specific

emotional and psychosomatic disorders. I have to refer the interested

reader to my earlier publication where I did this in considerable detail

(Grof 1985). In this context, I can only emphasize that the new conceptual

framework offers much more complete and convincing explanations for many

forms of 'psychopathology' and their various aspects that could not be

adequately accounted for by the existing schools of depth psychology.

3. Therapeutic mechanisms and the process of healing.

The new understanding of the dimensions of the human psyche and of the

architecture of emotional and psychosomatic disorders described above has

profound implications for therapy. Traditional psychotherapy knows only

therapeutic mechanisms operating on the level of biographical material,

such as remembering of forgotten events, lifting of repression,

reconstruction of the past from dreams, reliving of traumatic memories from

childhood, and analysis of transference. The work with holotropic states

reveals many important additional mechanisms of healing and personality

transformation that become available when our consciousness reaches the

perinatal and transpersonal levels.

This approach can be referred to as holotropic strategy of psychotherapy.

It represents an important alternative to the techniques of various schools

of depth psychology, which emphasize verbal exchange between the therapist

and the client, as well as to those experiential therapies that are

conducted in ordinary states of consciousness. The basic tenet of

holotropic therapy is that symptoms of emotional disorders represent an

attempt of the organism to free itself from old traumatic imprints, heal

itself, and simplify its functioning. They are not only a nuisance and

complication of life, but also a major opportunity.

Effective therapy then consists in temporary activation, intensification,

and subsequent resolution of the symptoms. This is a principle that

holotropic therapy shares with homeopathy. A homeopathic therapist has the

task to identify and apply the remedy that in healthy individuals during

the so called proofing produces the symptoms that the client manifests

(Vithoulkas 1980). The holotropic state of consciousness tends to function

as a universal homeopathic remedy in that it activates any existing

symptoms and exteriorizes symptoms that are latent.

This understanding does not apply only to neuroses and psychosomatic

disorders, but also to many conditions that mainstream psychiatrists would

diagnose as psychotic and see as manifestations of serious mental disease

(psychospiritual crises or 'spiritual emergencies'). The inability to

recognize the healing potential of such extreme conditions reflects the

narrow conceptual framework of Western psychiatry that is limited to

postnatal biography and the individual unconscious. Experiences for which

this framework does not provide a logical explanation are then attributed

to a pathological process of unknown origin.

Careful analysis of the phenomenology of 'spiritual emergencies' shows that

they constitute various combinations of perinatal, transpersonal, and

biographical experiences. Since the new extended cartography includes the

elements of all these domains, a conceptual framework that incorporates it

does not have to explain the origin of the content of these episodes. Their

experiential elements belong to the deep levels of the human psyche per se,

understood in this comprehensive way (Jung's 'anima mundi').

The theoretical explanation only has to account for the fact that some

people have to get involved in systematic spiritual practice, breathe

faster, or take a psychedelic substance to get to these levels of the

psyche, whereas for others the deep contents emerge in the middle of their

everyday life. The specific patterns of the experiences constituting these

episodes can be understood from the general principles governing the

dynamics of the psyche (COEX systems, perinatal matrices, archetypal

dynamics, etc.)

4. The strategy of psychotherapy and self-exploration.

The goal in traditional psychotherapies is to reach an intellectual

understanding of how the psyche functions and why the symptoms develop and

to derive from this understanding a technique and strategy that would make

it possible to correct thei emotional functioning of the clients. A serious

problem with this approach is the remarkable lack of agreement among

psychologists and psychiatrists about fundamental issues, resulting in an

astonishing number of competing schools of psychotherapy. The work with

holotropic states shows us a surprising radical alternative - mobilization

of deep inner intelligence of the clients themselves that guides the

process of healing and transformation.

An important assumption of holotropic strategy of therapy is that an

average person in our culture operates in a way that is far below his or

her real potential and capacity. This impoverishment is due to the fact

that they identify with only one aspect of their being, the physical body

and the ego. This false identification leads to an inauthentic, unhealthy,

and unfulfilling way of life and contributes to the development of

emotional and psychosomatic disorders of psychological origin. The

appearance of distressing symptoms that do not have any organic basis can

be seen as an indication that the individual operating on false premises

has reached a point where it became obvious that the old way of being in

the world does not work any more and has become untenable.

As the orientation toward the external world collapses, the contents of the

unconscious start emerging into consciousness. Such a breakdown can occur

in a certain limited area of life - such as marriage and sexual life,

professional orientation, and pursuit of various personal ambitions - or

afflict simultaneously the totality of the individual's life. The extent

and depth of this breakdown correlates approximately with the seriousness

of the resulting condition - development of neurotic or psychotic

phenomena. Such a situation represents a crisis or even emergency, but

also a great opportunity.

The main objective of holotropic strategy of therapy is to activate the

unconscious and free the energy bound in emotional and psychosomatic

symptoms, which converts these symptoms into a stream of experience. The

task of the facilitator or therapist in holotropic therapy then is to

support the experiential process with full trust in its healing nature,

without trying to direct it or change it. This process is guided by the

client's own inner healing intelligence. The term therapist is used here in

the sense of the Greek therapeutes, which means the person assisting in the

healing process, not an active agent whose task is to 'fix the client.'

Some powerful healing and transforming experiences might not have any

specific content at all; they consist of sequences of intense build-up of

emotions or physical tensions and subsequent deep release and relaxation.

Frequently the insights and specific contents emerge later in the process,

or even in the following sessions. In some instances the resolution occurs

on the biographical level, in others in connection with perinatal material

or with various transpersonal themes.

Dramatic healing and personality transformation with lasting effects often

result from experiences that altogether elude rational understanding. It is

important for the therapist to support the experiential unfolding, even if

he or she does not rationally understand it. Naturally, with increasing

experience, the therapist accumulates significant knowledge of the general

principles underlying this process, but this does not save him or her from

surprises. The dynamics of the psyche is exquisitely creative and cannot be

captured in a set of rigid routinely applicable formulas.

5. The role of spirituality in human life.

In the world view of Western materialistic science only matter really

exists and there is no place for any form of spirituality. Being spiritual

is seen as an indication of lack of education, superstition, primitive

magical thinking, wishful fantasies, and emotional immaturity. Direct

experiences of spiritual dimensions of reality are seen as manifestations

of serious mental disease, psychosis. Research of holotropic states of

consciousness has brought evidence that, properly understood and practiced,

spirituality is a natural and important dimension of the human psyche and

of the universal scheme of things.

To prevent confusion and misunderstanding that in the past have plagued

discussions about spiritual life and have created a false conflict between

religion and science, it is critical to make a clear distinction between

spirituality and religion. Spirituality is based on direct experiences of

ordinarily hidden dimensions of reality. It does not necessarily require a

special place, or a special person mediating contact with the divine,

although mystics can certainly benefit from spiritual guidance and a

community of fellow seekers. Spirituality involves a special relationship

between the individual and the cosmos and is in its essence a personal and

private affair. At the inception of all great religions were visionary

(perinatal and transpersonal) experiences of their founders, prophets,

saints, and even ordinary followers. All major spiritual scriptures -- the

Vedas, the Buddhist Pali Canon, the Bible, the Koran, the Book of Mormon,

and many others are based on revelations in holotropic states.

By comparison, the basis of organized religion is institutionalized group

activity that takes place in a designated location (temple, church,

synagogue), and involves a system of appointed mediators. Ideally,

religions should provide for its members access to and support for direct

spiritual experiences. However, it often happens that, once it becomes

organized, a religion more or less loses the connection with its spiritual

source and becomes a secular institution exploiting the human spiritual

needs without satisfying them. Instead, it creates a hierarchical system

focusing on the pursuit of power, control, politics, money, and other

possessions. Under these circumstances, religious hierarchy tends to

actively discourage and suppress direct spiritual experiences of its

members, because they foster independence and cannot be effectively

controled.

The observations from the study of holotropic states confirm the ideas of

C. G. Jung concerning spirituality. According to him, the experiences from