Three of the four views which I will classify here as "materialist" or "physicalist" (see section 3 above) admit the existence of mental processes, and especially of consciousness, but all four assert that the physical world — what I am calling "World 1" — is self-contained or closed. By this I mean that physical processes can be explained and understood, and must be explained and understood, entirely in terms of physical theories.

I call this the physicalist principle of the closedness of the physical World 1. It is of decisive importance, and I take it as the characteristic principle of physicalism or materialism.

I have earlier suggested that we are faced with a prima facie dualism or pluralism, with interaction between World 1 and World 2; moreover, I have suggested that by way of the mediation of World 2, World 3 can act upon World 1. By contrast, the physicalist principle of the closedness of World 1 either asserts that there is only a World 1 or implies that if there is anything like a World 2 or a World 3 it cannot act upon World 1: World 1 is self-contained or closed. This position is intrinsically convincing. Most physicists would be inclined to accept it without question. But is it true? And are we able, if we accept it, to provide an adequate alternative explanation of our prima facie dualism? In the present chapter, I will suggest that the theories produced by materialists to date are unsatisfactory, and that there is no reason to reject our prima facie view; a view that is inconsistent with the physicalist principle. (It might be added that, in my opinion, the openness of the physical world is needed to explain — rather than explain away — human freedom. See my [1973 (a)].)

In this introductory section I will distinguish the following four materialist or physicalist positions:

(1) Radical Materialism or Physicalism, or Radical Behaviourism. This is the view that conscious processes and mental processes do not exist: their existence can be "repudiated" (to use a term of W. V. Quine's).

I do not think that many materialists have held this view in the past (see section 56 below), for it stands in flagrant opposition to, or tries in the end to explain away, what to most of us appear as undeniable facts, such as (subjective) pain and suffering. The great classical systems of materialism, from the early Greek materialists to Hobbes and La Mettrie, are not "radical" in the sense of denying the existence of conscious or mental processes. Nor is the "dialectical materialism" of Marx and Lenin "radical" in this sense, or the behaviourism of most behaviourist psychologists.1

Nevertheless, what I call radical materialism (or radical physicalism or radical behaviourism) is an important position which must not be neglected. First, because it is consistent in itself. Secondly, because it presents a very simple solution of the mind-body problem: the problem clearly disappears if there is no mind, but only body.2 (Of course, the problem also disappears if we adopt a radical spiritualism or idealism, such as the phenomenalism of Berkeley or Mach, that denies the existence of matter.) Thirdly, because in the light of evolutionary theory, matter, and especially chemical processes, existed before mental processes existed. Current theories suggest that the evolution and the development of the body come before the evolution and the development of the mind; and they are the basis of the evolution and the development of the mind. Since this is so, it is understandable that, under the impact of contemporary science, we might perhaps become radical physicalists if we are strongly inclined towards monism and simplicity, and do not wish to accept a dualist or a pluralist view of things.

It is for reasons such as these that a radical physicalism or a radical behaviourism is accepted by some outstanding philosophers such as Quine ([1960], p.264; [1975], pp. 93ff.); and it is now often suggested by others that something very much like a radical physicalism or behaviourism will ultimately have to be accepted, perhaps because of the results of science or of philosophical analysis. Suggestions such as these, though not always unambiguous ones, can be found for example in the works of Ryle [1949], [1950] or of Wittgenstein [1953]; of Hilary Putnam [1960] or of J.J.C. Smart [1963]. Indeed one may perhaps say that, at the time of writing, radical materialism or behaviourism seems to be the view concerning the mind-body problem that is most fashionable among the younger generation of students of philosophy. Thus it has to be discussed.

My criticism of radical materialism or radical behaviourism will be along three lines. First, I will argue that, by denying the existence of consciousness, this view of the world simplifies cosmology — but it does so by omitting rather than by solving its greatest and most interesting riddle. Further, I will argue that a principle which many adopt as "scientific", and which speaks in favour of radical behaviourism, springs from a misunderstanding of the method of the natural sciences. And lastly I will argue that this view is false, and that it is refuted by experiment (although, of course, a refutation can always be evaded).2

(2) All the other views which I classify here as materialistic admit the existence of mental processes and, especially, of conscious processes: they admit what I call World 2. However, they also accept the fundamental principle of physicalism — the closedness of World 1.

The oldest of these views, panpsychism, goes back to the earliest Pre-socratics and to Campanella. It was elaborately presented in Spinoza's Ethics, and in Leibniz's Monadology.

Panpsychism is the view that all matter has an inside aspect which is a soul-like or a consciousness-like "quality". Thus for panpsychism, matter and mind run "parallel" like the outside and the inside aspects of an eggshell (Spinozistic parallelism). In non-living matter, the inside aspect may not be conscious: the soul-like precursor of consciousness may be described as "pre-psychical" or "proto-psychical". With the integration of atoms into giant molecules and living matter, memory-like effects emerge; and with the higher animals, consciousness emerges.

Panpsychism was defended in Britain especially by the mathematician and philosopher William Kingdon Clifford [1879], [1886], Clifford teaches (not unlike Leibniz's form of parallelism) that things in themselves are mind-stuff (pre-psychical or else psychical) but that, observed from the outside, they appear as matter.3

Panpsychism shares with radical materialism a certain simplicity of outlook. The universe is in both cases homogeneous and monistic. Their motto could well be: "There really is no new thing under the sun", which indicates an intellectually comfortable way of living — though not an intellectually very exciting one. But everything in the universe seems to fit very nicely once the radical materialistic view, or the panpsychistic view, is adopted.

(3) Epiphenomenalism may be interpreted as a modification of panpsychism, in which the "pan" element is dropped and the "psychism" is confined to those living things that seem to have a mind. Like panpsychism it is, in its usual form, a variety of parallelism; that is to say, of the view that mental processes run parallel with certain physical processes — say, because they are the inside and the outside views of some (unknown) third entity.

However, there may be forms of epiphenomenalism which are not parallelist: what I take to be essential in epiphenomenalism is the thesis that only the physical processes are causally relevant with respect to later physical processes, while the mental processes, though existing, are causally completely irrelevant.

(4) The identity theory, or the central state theory, is at present the most influential of the theories developed in response to the mind-body problem. It may be regarded as a modification of both panpsychism and epiphenomenalism. Like epiphenomenalism, it can be seen as panpsychism without the "pan". But as opposed to epiphenomenalism it takes mental facts as important and as causally effective. It asserts that there is some kind of "identity" between mental processes and certain brain processes: not an identity in the logical sense, but still an identity such as that between "the evening star" and "the morning star" which are alternative names for one and the same planet, Venus; though they also denote different appearances of the planet Venus. In one form of the identity theory, a form due to Schlick and Feigl, the mental processes are regarded (as by Leibniz) as things in themselves, known by acquaintance, from the inside, while our theories about brain processes — processes of which we know only by theoretical description — happen to describe the same things from the outside. In contrast to an epiphenomenalist, the identity theorist can say that mental processes interact with physical processes, for the mental processes simply are physical processes; or more precisely, special kinds of brain processes.

In section 10 above, I discussed, briefly, the example of a visit to the dentist, to illustrate the way in which physical states (World 1), our conscious awareness (World 2), and plans and institutions (World 3) are all involved in such actions. The character of our four materialistic theories may be illustrated by the way in which they would give an account of such an incident. It might involve, for example, our damaging a tooth, our developing a toothache, our 'phoning the dentist to make an appointment, and our subsequent visit to him in order to obtain treatment.

(1) Radical materialist interpretation: there are processes in my tooth leading to processes in my nervous system. Everything that happens consists of physical processes confined to World 1 (including my verbal behaviour — my uttering words on the telephone).

(2) Panpsychistic interpretation: there are the same physical processes as in (1), but there is also another side to the story. There is a "parallel" account (which various panpsychists may explain in different ways) which tells the story as it is experienced by us. Panpsychism tells us not only that our experience in some way "corresponds" to the physical explanation as given in (1), but that the apparently purely physical objects involved (such as the telephone) have also an "inner aspect", more or less similar to our own inner awareness.

(3) Epiphenomenalist interpretation: there are the same physical processes as in (1), and the rest of the story is not unlike (2). But there are the following differences from (2): (a) only the "animate" objects have "inner" or subjective experiences; (b) whereas in (2) it was suggested that we have two different but equally valid accounts, the epiphenomenalist not only gives priority to the physical account, but emphasizes that subjective experiences are causally redundant: my felt pain plays no causal role whatever in the story; it does not motivate my action.

(4) Identity theory: the same as in (1), but this time we can distinguish between those World 1 processes which are not identical with conscious experiences (World lp: the subscript p stands for "purely physical") and those physical processes which are identical with experienced or conscious processes (World lm: the subscript m stands for "mental"). The two parts of World 1 (that is to say, the sub-worlds \p and lm) can, of course, interact. Thus my pain (World 1 m) acts upon my memory store and this makes me look up the telephone number. Everything happens as in the interactionist analysis (this is, I think, what makes this view attractive) only my World 2 (including subjective knowledge) is identified with World lm, that is, with a part of World 1, and World 3 is identified with other parts of World 1: with instruments, or gadgets, such as the telephone directory or the telephone (or perhaps with brain processes: for the identity theorist abstract knowledge contents, which are the heart of my World 3, do not exist).

1 Compare, on this, the remark about Marx on p. 102 of volume II of my Open Society [1966 (a)], and the remarks on the Stoics in footnotes 6 and 7 on p. 157 of my [1972 (a)].

2 Some radical materialists do, however, take the problem seriously. See section 25 below.

2 See my [1959 (a)], sections 19-20.

3 Clifford mentions several German philosophers as precursors of his view. Thus, in ([1886], p.286) he refers to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. Clifford refers to Rosenkranz's edition, which reprints the text of the first edition of the Critique; see note 1 to section 22 below. Clifford also mentions Wilhelm Wundt ([1880], volume II, pp. 460ff.) and Ernst Haeckel [1878]. Later representatives of panpsychism in Germany are Theodor Ziehen [1913], and Bernhard Rensch [1968], [1971], The identity theory of Moritz Schlick and Herbert Feigl shows a certain similarity to panpsychism, although they do not seem to discuss the evolutionary aspects of the problem, and therefore do not say that the "things in themselves", or the "qualitites", of non-living things are pre-psychical in character. (See also section 54 below.)

What does World 3 look like from a materialistic point of view? Obviously, the bare existence of aeroplanes, airports, bicycles, books, buildings, cars, computers, gramophones, lectures, manuscripts, paintings, sculptures and telephones presents no problem for any form of physicalism or materialism. While to the pluralist these are the material instances, the embodiments, of World 3 objects, to the materialist they are simply parts of World 1.

But what about the objective logical relations which hold between theories (whether written down or not), such as incompatibility, mutual deducibility, partial overlapping, etc.? The radical materialist replaces World 2 objects (subjective experiences) by brain processes. Especially important among these are dispositions for verbal behaviour: dispositions to assent or reject, to support or refute; or merely to consider — to rehearse the pros and cons. Like most of those who accept World 2 objects (the "mentalists"), materialists usually interpret World 3 contents as if they were "ideas in our minds": but the radical materialists try, further, to interpret "ideas in our minds" - and thus also World 3 objects - as brain-based dispositions to verbal behaviour.

Yet neither the mentalist nor the materialist can in this way do justice to World 3 objects, especially to the contents of theories, and to their objective logical relations.

World 3 objects just are not "ideas in our minds", nor are they dispositions of our brains to verbal behaviour. And it does not help if one adds to these dispositions the embodiments of World 3, as mentioned in the first paragraph of this section. For none of these copes adequately with the abstract character of World 3 objects, and especially with the logical relations existing between them.4

As an example, Frege's Grundgesetze was written, and partly printed, when he deduced, from a letter written by Bertrand Russell, that there was a self-contradiction involved in its foundation. This self-contradiction had been there, objectively, for years. Frege had not noticed it: it had not been "in his mind". Russell only noticed the problem (in connection with quite a different manuscript) at a time when Frege's manuscript was complete. Thus there existed for years a theory of Frege's (and a similar more recent one of Russell's) which was objectively inconsistent without anyone's having an inkling of this fact, or without anyone's brain state disposing him to agree to the suggestion "This manuscript contains an inconsistent theory".

To sum up, World 3 objects and their properties and relations cannot be reduced to World 2 objects. Nor can they be reduced to brain states or dispositions; not even if we were to admit that all mental states and processes can be reduced to brain states and processes. This is so despite the fact that we can regard World 3 as the product of human minds.

Russell did not invent or produce the inconsistency, but he discovered it. (He invented, or produced a way of showing or proving that the inconsistency was there.) Had Frege's theory not been objectively inconsistent, he could not have applied Russell's inconsistency proof to it, and he would not have thus convinced himself of its untenability. Thus a state of Frege's mind (and no doubt also a state of Frege's brain) was the result, partly, of the objective fact that this theory was inconsistent: he was deeply upset and shaken by his discovery of this fact. This, in turn, led to his writing (a physical World 1 event) the words, "Die ArithmetikistinsSchwankengeraten"("Arithmetic is tottering"). Thus there is interaction between (a) the physical, or partly physical, event of Frege's receiving Russell's letter; (b) the objective hitherto unnoticed fact, belonging to World 3, that there was an inconsistency in Frege's theory; and (c) the physical, or partly physical, event of Frege's writing his comment on the (World 3) status of arithmetic.

These are some of the reasons why I hold that World 1 is not causally closed, and why I assert that there is interaction (though an indirect one) between World 1 and World 3. It seems to me clear that this interaction is mediated by mental, and partly even conscious, World 2 events.

The physicalist, of course, cannot admit any of this.

I believe that the physicalist is also prevented from solving another problem: he cannot do justice to the higher functions of language.

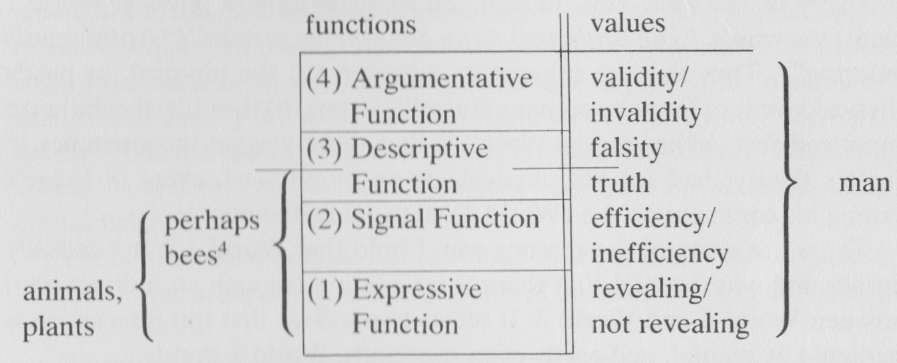

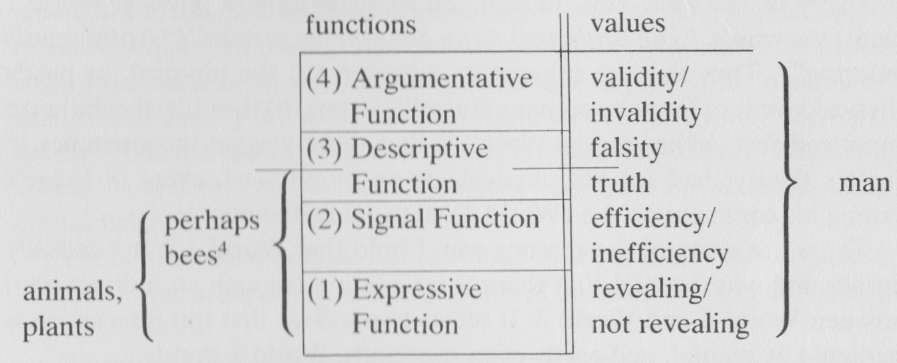

This criticism of physicalism relates to the analysis of the functions of language that was introduced by my teacher, Karl Buehler. He distinguished three functions of language: (1) the expressive function; (2) the signal or release function; and (3) the descriptive function (see Buehler [1918]; [1934], p. 28). I have discussed Buehler's theory in various places,5 and I have added to his three functions a fourth — (4) the argumentative function. Now I have argued elsewhere3 that the physicalist is only able to cope with the first and the second of these functions. As a result, if faced with the descriptive and the argumentative functions of language, the physicalist will always see only the first two functions (which are also always present), with disastrous results.

In order to see what is at issue, it is necessary to discuss briefly the theory of the functions of language.

In Buehler's analysis of the act of speech he differentiates between the speaker (or, as Buehler also calls him, the sender) and the person spoken to, the listener (or the receiver). In certain special ("degenerate") cases the receiver may be missing, or he may be identical with the sender. The four functions here discussed (there are others, such as command, exhortation, advice — see also John Austin's [1962] "performative utterances") are based on relations between (a) the sender, (b) the receiver, (c) some other objects or states of affairs which, in degenerate cases, may be identical with (a) or (b). I will give a table of the functions in which the lower functions are placed lower and the higher functions higher.

The following comments may be made on this table:

(1) The expressive function consists in an outward expression of an inner state. Even simple instruments such as a thermometer or a traffic light "express" their states in this sense. However, not only instruments, but also animals (and sometimes plants) express their inner state in their behaviour. And so do men, of course. In fact, any action we undertake, not merely the use of a language, is a form of self-expression.

(2) The signalling function (Buehler calls it also the "release function") presupposes the expressive function, and is therefore on a higher level. The thermometer may signal to us that it is very cold. The traffic light is a signalling instrument (though it may continue to work during hours where there may not always be cars about). Animals, especially birds, give danger signals; and even plants signal (for example to insects); and when our self-expression (whether linguistic or otherwise) leads to a reaction, in an animal or in a man, we can say that it was taken as a signal.

(3) The descriptive function of language presupposes the two lower functions. What characterizes it, however, is that over and above expressing and communicating (which may become quite unimportant aspects of the situation), it makes statements that can be true or false: the standards of truth and falsity are introduced. (We may distinguish a lower half of the descriptive function where false descriptions are beyond the animal's (the bee's?) power of abstraction. Also a thermograph would belong here, for it describes the truth unless it breaks down.)

(4) The argumentative function adds argument to the three lower functions, with its values of validity and invalidity.

Now, functions (1) and (2) are almost always present in human language; but they are as a rule unimportant, at least when compared with the descriptive and argumentative functions.

However, when the radical physicalist and the radical behaviourist turn to the analysis of human language, they cannot get beyond the first two functions (see my [1953 (a)]). The physicalist will try to give a physical explanation — a causal explanation — of language phenomena. This is equivalent to interpreting language as expressive of the state of the speaker, and therefore as having the expressive function alone. The behaviourist, on the other hand, will concern himself also with the social aspect of language — but this will be taken, essentially, as affecting the behaviour of others; as "communication", to use a vogue word; as the way in which speakers respond to one another's "verbal behaviour". This amounts to seeing language as expression and communication.

But the consequences of this are disastrous. For if all language is seen as merely expression and communication, then one neglects all that is characteristic of human language in contradistinction to animal language: its ability to make true and false statements, and to produce valid and invalid arguments. This, in its turn, has the consequence that the physicalist is prevented from accounting for the difference between propaganda, verbal intimidation, and rational argument.

It might also be mentioned that the characteristic openness of human language — the capacity for an almost infinite variety of responses to any given situation, to which Noam Chomsky, particularly, has forcefully drawn our attention — is related to the descriptive function of language. The picture of language — and of the acquisition of language — as offered by behaviouristically inclined philosophers such as Quine seems, in fact, to be a picture of the signalling function of language. This, characteristically, is dependent upon the prevailing situation. As Chomsky has argued [1969] the behaviourist account does not do justice to the fact that a descriptive statement can be largely independent of the situation in which it is used.

4 For a fuller discussion of this, see section 21, below.

5 For example, my [1963 (a)], chapters 4 and 12; [1972 (a)], chapters 2 and 6.

4 The dancing bees may perhaps be said to convey factual or descriptive information. A thermograph or barograph does so in writing. It is interesting that in both cases the problem of lying does not seem to arise — although the maker of the thermograph may use it to misinform us.

Radical materialism or radical physicalism is certainly a selfconsistent position. For it is a view of the universe which, as far as we know, was adequate once; that is, before the emergence of life and consciousness.

There is a slight awkwardness felt by most of those who hold and defend this theory now: the very fact that they propose a theory (qua theory), their own belief, their own words, their own arguments, all seem to contradict it. In order to get over this difficulty, the radical physicalist must adopt radical behaviourism and apply it to himself: his theory, his belief in it, is nothing; only the physical expression in words, and perhaps in arguments — his verbal behaviour and the dispositional states that lead to it — is something.

What speaks in favour of radical materialism or radical physicalism is, of course, that it offers us a simple vision of a simple universe, and this looks attractive just because, in science, we search for simple theories. However, I think that it is important that we note that there are two different ways by which we can search for simplicity. They may be called, briefly, philosophical reduction and scientific reduction.6 The former is characterized by an attempt to simplify our view of the world; the second by an attempt to provide bold and testable theories of high explanatory power.71 believe that the latter is an extremely valuable and worthwhile method; while the former is of value only if we have good reasons to assume that it corresponds to the facts about the universe.

Indeed, the demand for simplicity in the sense of philosophical rather than scientific reduction may actually be damaging. For even in order to attempt a scientific reduction, it is necessary for us first to get a full grasp of the problem to be solved, and it is therefore vitally important that interesting problems are not "explained away" by philosophical analysis. If, say, more than one factor is responsible for some effect, it is important that we do not pre-empt the scientific judgement: there is always the danger that we might refuse to admit any ideas other than the ones we happen to have at hand; explaining away, or belittling the problem. The danger is increased if we try to settle the matter in advance by philosophical reduction. Philosophical reduction also makes us blind to the significance of scientific reduction.8

It is in this light that I think we should consider the radical physicalist's approach to the problem of consciousness. Not only do we have, in the phenomena of consciousness, something that seems radically different from what, on our current view, is to be found in the physical world. We also have the dramatic and, from a physical point of view, strange changes that have taken place in the physical environment of man, due, it appears, to conscious and purposeful action. This should not be ignored, or dogmatically explained away.

I would even suggest that the greatest riddle of cosmology may well be neither the original big bang, nor the problem why there is something rather than nothing (it is quite possible that these problems may turn out to be pseudoproblems), but that the universe is, in a sense, creative: that it created life, and from it mind — our consciousness — which illuminates the universe, and which is creative in its turn. It is one of the high points in Herbert Feigl's Postscript [1967] to his essay The 'Mental' and the 'Physical' when he relates how, in a conversation, Einstein said something like this: "If there were not this internal illumination, the universe would merely be a rubbish heap."9This, Feigl tells us, is one of the reasons why he does not accept radical physicalism (as I call it) but the identity theory, which recognizes the reality of mental and especially of conscious processes.

It might also be worth bearing in mind that, while in science, our quest is for simplicity, it is a real problem whether the world is itself quite so simple as some philosophers think. The simplicity of the old theory of matter (that of Descartes or that of Newton or even that of Boscovich) is gone: it clashed with the facts. The same happened to the electrical theory of matter which, for twenty or thirty years, seemed to offer a hope of an even greater simplicity. Our present theory of matter, quantum mechanics, turns out (especially in the light of the thought experiment of Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen, and the results of J. Bell, and of S.J. Freedman and R. A. Holt [1975]) to be even less simple than one might have hoped. It is also clearly incomplete: in spite of Dirac's result which may be interpreted as the prediction of anti-particles, quantum theory cannot be said to have led to the prediction or explanation of the many new elementary particles which have been found in recent years. Thus appeals to simplicity can hardly be accepted as decisive, not even within physics. In particular, we should not deprive ourselves of interesting and challenging problems — problems that seem to indicate that our best theories are incorrect and incomplete — by persuading ourselves that the world would be simpler if they were not there. But it seems to me that modern materialists are doing just this.10

I may say here perhaps that I should regard radical physicalism, if it were compatible with the facts, as an intellectually satisfying theory. But it is not compatible with the facts. And the facts, difficult as they are to absorb, are intellectually challenging. So to me the decision seems to be between intellectual ease (or let us call it smugness) and unease.

Radical behaviourism, on which the radical physicalist must depend in order to explain to himself his theoretical activities as "verbal behaviour", derives most of its appeal from a misunderstanding of a problem of method. The behaviourist demands, rightly, that any scientific theory, and therefore also the theories of psychology, must be testable by reproducible experiments, or at least by intersubjectively testable observation statements: by statements about observable behaviour, which in the case of human psychology includes verbal behaviour.

But this important principle refers only to the test statements of a science. Just as in physics we introduce theoretical entities — electrons and other particles, or fields of forces, etc. — in order to explain our observation statements (about photographs of the events in bubble chambers, for example), so we can introduce, in psychology, conscious and unconscious mental events and processes, if these are helpful in explaining human behaviour, such as verbal behaviour. In this case, the attribution of a mind and of subjective conscious experiences to every normal human person is an explanatory theory of psychology of about the same character as the existence of relatively stable material bodies in physics. In both cases the theoretical entities are not introduced as something ultimate — as substances in the traditional sense; both create vast regions of unsolved problems, and so does their interaction. But in both cases our theories are well testable: in physics, by the experiments of mechanics; in psychology, by certain experiments

which lead to reproducible verbal reports (and thus to reproducible "verbal behaviour"). Since all, or almost all, experimental subjects react in these experiments with recognizably the same reports — reports about what they subjectively experience in the experimental situation — the theory of their having these subjective experiences is well tested.

I will here describe a simple experiment which every reader can carry out himself, and check with any of his friends. It is taken from the work of the great Danish experimental psychologist, Edgar Rubin ([1950], pp. 366 f.). I use optical illusions because here the character of subjective experiences becomes very clear.

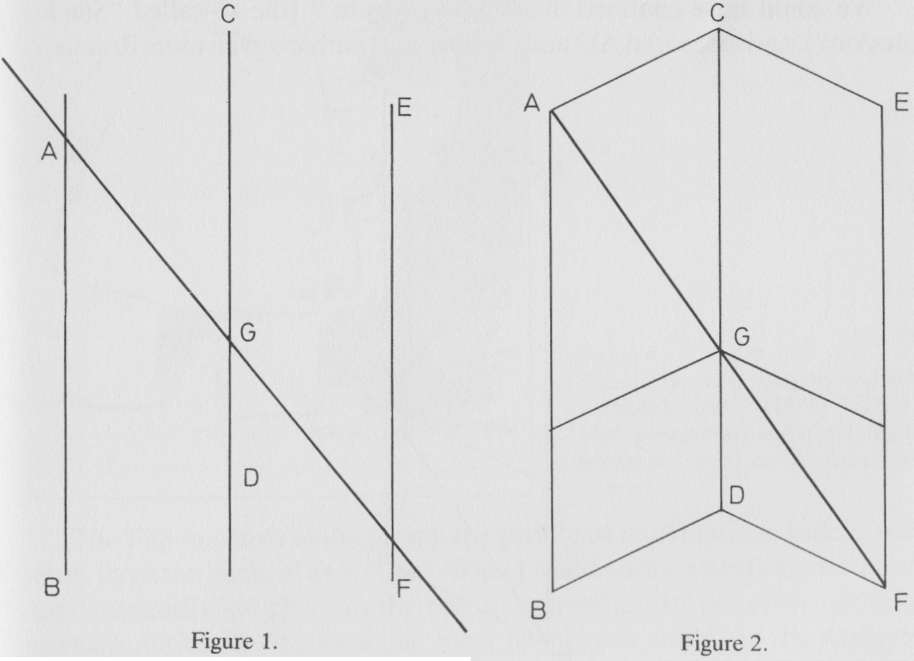

The following two figures are taken from Rubin, with very slight changes.

It will be seen from Figure 1 that, since AB, CD, and EF are parallel and equidistant, the inclined line AF is cut in half at G; so that AG = GF.

We explain all this to our experimental subject, who thus does not need to measure the distances AG and GF in order to make sure that they are equal.

We now put to him the following questions.

(1) Look at Figure 2. You know that AG = GF, in view of the proof indicated by Figure 1. Do you agree?

We wait for the reply.

(2) Does AG look to you equal to GF?

We wait again for the reply.

Question (2) is the decisive question. The reply ("No") which is obtained from every (or almost every) experimental subject can be explained most directly by the conjecture that the subjective visual experience of every subject deviates systematically from what we all know (and can prove) to be objectively the case. This establishes an easily repeatable objective and behavioural test of the existence of subjective experience. (Of course, only as long as we take the reports of our experimental subjects seriously; but the radical behaviourist can still reinterpret ad hoc their verbal responses: every falsification can be evaded by one who is not prepared to learn from experience.)

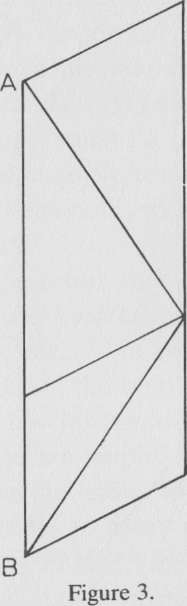

We could have confined ourselves to Figure 3 (the so-called "Sanders Illusion"), and measured AG and GB, which is perhaps even more dramatic.

Yet measurements may leave some doubt: small errors may matter and may not be easily detectable. On the other hand, it is clear that the three vertical lines in Figure 1 and Figure 2 are parallel and equi-distant. A further question is:

(3) Does your theoretical knowledge with respect to Figure 2 help you to see the distances AG and GF as equal?

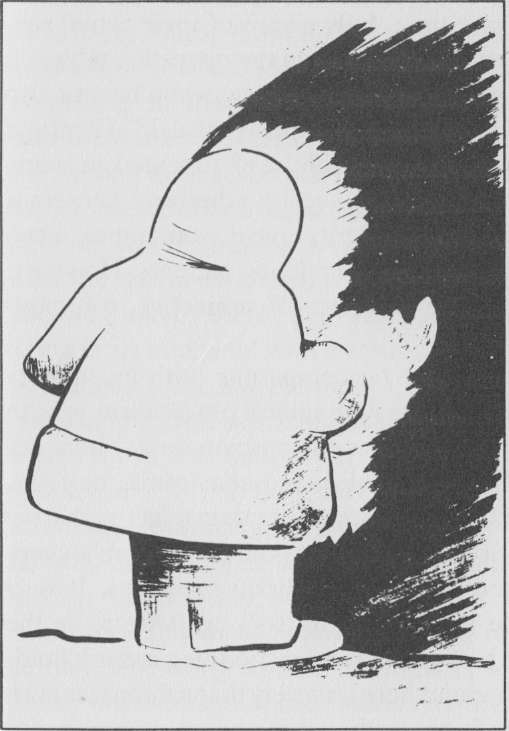

A related but slightly different experiment may convince us that our mental processes are often mental activities. It operates with an ambiguous figure. (Such figures are used in Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations, yet, it seems, with very different aims or purposes.) The figure used (the "Winson Figure") is taken from a paper by Ernst Gombrich ([1973], p. 239).

Figure 4. Taken from R. L. Gregory and E. H. Gombrich (eds.) [1973] with the kind permission of the author, the publisher, and of Alphabet and Image.

The Figure shows ambiguously the profile of an American Indian and a view, from the back, of an Eskimo. What I wish to draw attention to is that we can voluntarily switch from the one interpretation to the other, although perhaps not easily. It seems that most people can easily see the American Indian and have difficulties in switching over to the Eskimo. (However, it is the other way round for some people.)

Now the point is that we can voluntarily and actively build up the profile of the Indian by looking at his nose, mouth, and chin, and then proceeding to his eye. As to the Eskimo, we can start to build him up from his right boot. (And of course, we can formulate experimental questions about these activities which lead to intersubjectively repeatable answers.)

There are also other sorts of intersubjectively testable experiments which are most successful and convincing tests of the theory that men have conscions experiences. For example, there are the experiments conducted by the great brain surgeon Wilder Penfield. Penfield [1955] repeatedly stimulated, with the help of an electrode, the exposed brain of patients who were being operated on while fully conscious. When certain areas of the cortex were thus stimulated, the patients reported re-living very vivid visual and auditive experiences while being, at the same time, fully aware of their actual surroundings. "A young South African patient lying on the operating table . . . was laughing with his cousins on a farm in South Africa, while he was also fully conscious of being in the operating room in Montreal." (Penfield [1975], p. 55.) Such reports, clearly reproducible, and repeated in many cases, can be only explained so far as I can see by admitting conscious subjective experiences. Penfield's experiments have sometimes been criticized for having been conducted only with epileptic patients. However, this does not affect the problem of the existence of subjective, conscious experiences.

These experiments of Penfield's may be compatible with an identity theory. They do not seem to be compatible with radical physicalism — with the denial of the existence of subjective states of consciousness. There are many similar experiments.11 They test and establish, by behaviourist methods, the conjecture — if it is to be called a conjecture rather than a fact — that we have subjective experiences; conscious processes. Admittedly, there is every reason to think that these go hand in hand with brain processes. It is, it appears, the brain rather than the self which "insists", as it were, on the inequality of distances we know to be equal. (A corresponding remark holds for the Gestalt switch.) Yet my main point here is merely that we can establish empirically, by behaviourist methods, that subjective, conscious experience exists.

A word may be added on the unusual or paradoxical character of both types of experiment here mentioned — optical illusion and Penfield's stimulation of the cortex. Our mechanism of perception is normally not reflexively directed onto itself, but directed towards the outside world. Thus we can forget about ourselves in normal perception. In order to become quite clear about our subjective experience it is therefore useful to choose experiments in which something is out of the ordinary and clashes with the normal perceptual mechanism.

6 See my [1972 (a)], chapter 8, where these ideas are discussed in more detail.

7 See, for example, my [1972 (a)], chapter 5.

8 Consider, for example, what a dogmatic philosophical reductionist of a mechanistic disposition (or even a quantum-mechanistic disposition) might have done in the face of the problem of the chemical bond. The actual reduction, so far as it goes, of the theory of the hydrogen bond to quantum mechanics is far more interesting than the philosophical assertion that such a reduction will one day be achieved.

9 Cp. Feigl [1967], p. 138. Feigl translates a German conversation; I have slightly changed the wording of the translation (as Feigl also did, according to his report).

10 5 It might be mentioned that the conflict described in the text could also be seen as the conflict between conventionalism and realism in the philosophy of science. Perhaps Charles S. Sherrington ([1947], p. xxiv) may be quoted here: "That our being should consist of two fundamental elements offers I suppose no greater inherent improbability than that it should rest on one only."

11 One important type of experiment is due to modern sleep research: rapid eye movements have been shown to indicate dreaming; and dreaming is clearly a (low-level) conscious experience. (The radical behaviourist or materialist would have to say, in order to avoid refutation, that rapid eye movements signify a manifestation of a disposition which would lead people if woken up to say that they had been dreaming (while in reality no such things as dreams exist). But this would obviously be an ad hoc way of evading refutation.)

Panpsychism is a very ancient theory. Traces of it can be found in the earliest Greek philosophers (who are often described as "hylozoists", that is, as holding that all things are animate). Aristotle reports of Thales (De anima 411a7; cp. Plato, Laws 899b) that he taught "Everything is full of gods". This may, Aristotle suggests, be a way of saying that "soul is mingled with everything in the whole universe", including what we usually regard as inanimate matter. This is the doctrine of panpsychism.

Among the Presocratic philosophers down to Democritus, panpsychism has a materialist or at least semi-materialist character in so far as the psyche, or mind, was regarded as a very special kind of matter. This attitude changes with the moral or ethical theory of the soul developed by Democritus, by Socrates, and by Plato. Yet even Plato ( Timaeus 30 b/c) calls the universe "a living body endowed with a soul".

Panpsychism, like pantheism, is widespread among Renaissance thinkers (for example Telesius, Campanella, Bruno). It is fully developed in Spinoza's treatment of the mind-body relationship, his doctrine of psycho-physical parallelism: ". . . all things are animate in various degrees". (Ethics II, XIII, Scholium.) According to Spinoza, matter and soul are the outside and inside aspects, or attributes, of one and the same thing in itself (or things in themselves); that is to say, of "Nature, which is the same as God".

A very similar yet atomist version of the theory is the monadology of Leibniz. The world consists of monads (= points), of unextended intensities. Being unextended, these intensities are souls. They are, as in Spinoza, animate in various degrees. The main difference from Spinoza's theory is this: while in Spinoza, the thing in itself is the (inscrutable) Nature, or God, of which body and soul are outside and inside aspects, Leibniz teaches that his monads — which are the things in themselves — are souls, or spirits, and that extended bodies (which are spatial integrals over the monads) are their outside appearances. Leibniz is therefore a metaphysical spiritualist: bodies are accumulations of spirits, seen from the outside.

Kant teaches, by contrast, that the things in themselves are unknowable. Yet there is a strong suggestion that, as moral characters, we ourselves are things in themselves; though there is also a suggestion that the other things in themselves (those which are not human) are not of a mental or spiritual character: Kant is not a panpsychist.

Schopenhauer takes up Kant's suggestion that as moral characters — as moral wills — we are things in themselves; and he generalizes this: the thing in itself (Spinoza's God) is will, and will manifests itself in all things. Will is the essence, the thing in itself, the reality of everything, and will is what, from outside, for the observer, appears as body or matter. One can say that Schopenhauer is a Kantian who has turned panpsychist. In order to carry out this idea, Schopenhauer emphasizes the unconscious: although his will is mental, or psychical, it is largely unconscious — completely so in inanimate matter, but largely so even in animals and in man. Schopenhauer is thus a spiritualist; but his spirit is mainly unconscious will, drive, and appetite, rather than conscious reason. This theory12 3exerted a great influence upon German, English and American panpsychists who, partly under the influence of Schopenhauer, interpret the chemical affinities, the binding forces of atoms, and other physical forces such as gravity, as the outward manifestations of the drive-like or will-like properties of the things in themselves which, seen from outside, appear to us as matter.

This may serve as a sketch of the idea of panpsychism.13 (An excellent historical and critical introduction by Paul Edwards may be found in his [1967 (a)].) Panpsychism has many varieties, and it offers what appears to its defenders a comfortable solution of the problem of the emergence of mind in the universe: mind was always there, as the inside aspect of matter. This seems to be the reason why panpsychism is accepted by several well-known contemporary biologists, such as C. H. Waddington [1961] in England or Bernhard Rensch [1968], [1971] in Germany.

It is obvious that panpsychism is, from a metaphysical (or ontological) point of view, nearer to spiritualism than to materialism. However, many panpsychists, from Spinoza and Leibniz to Waddington, Theodor Ziehen, and Rensch, accept what I called in section 16 above the physicalist principle of the closedness of the physical world. They believe,14 like Spinoza and Leibniz, that psychological or mental processes and physical or material processes run parallel, without interacting; that mental (World 2) processes can act only upon other mental processes, and that physical (World 1) processes can act only upon other physical processes, so that World 1 is closed, self-contained.

I will here present three arguments against panpsychism.

(1) My first criticism of panpsychism is that the assumption that there must be a pre-psychical precursor of psychical processes is either trivial and completely verbal, or grossly misleading. That there is something in evolutionary history which preceded, in some sense, the mental processes, is trivial as well as vague. But to insist that this something must be mind-like and that it can be attributed even to atoms is a misleading way of arguing. For we know that crystals and other solids have the property of solidity without solidity (or pre-solidity) being present in the liquid before crystallization (though the presence of a crystal or some other solid in the liquid may help in the crystallization process).

Thus we know of processes in nature which are "emergent" in the sense that they lead, not gradually but by something like a leap, to a property which was not there before. Although the mind of a baby develops, gradually, from a pre-mental state to full consciousness of self, we do not need to postulate that the food which the baby eats (and which in the end may form its brain) has qualities which can be, with informative success, described as pre-mental or as in any way even distantly similar to mind. Thus the pan-element in panpsychism seems to me gratuitous and also fantastic. (But I should not say that the idea shows much imagination.)

(2) Panpsychism accepts, of course, that what we usually call inanimate or inorganic matter has a very much poorer mental life than any organism. Thus to the great step from non-living to living matter will correspond a great step from pre-psychical processes to psychical processes. It is therefore not very clear how much panpsychism gains for a better understanding of the evolution of the mind by assuming pre-psychical states or processes: even on the panpsychistic account, something totally new enters the world with life, and with heredity, if only in several steps. Yet the main motive of post-Darwinian panpsychism was to avoid the need to admit the emergence of something totally novel.

To say this is not, of course, to deny the fact that there exist not only unconscious mental states, but also many different degrees of consciousness. There can be little doubt that dreaming is conscious, but on a low level of consciousness: it is a far cry from a dream to a critical evaluation and revision of a difficult argument. Similarly, a newborn child has clearly a low level of consciousness. It probably takes years, and the acquiring of language, and perhaps even of critical thinking, before the full consciousness of self is achieved.

(3) Although there exists, no doubt, something that may be described as unconscious memory — that is, memory of which we are not aware — there cannot be, I propose, consciousness or awareness without memory.

This may be explained with the help of a thought experiment.

It is well known that, as a consequence of an injury, or an electric shock, or a drug, a person may lose consciousness (and that a period of time prior to the event may be extinguished from his memory).

Now let us assume that, by taking a drug, or by some other treatment, we may extinguish the recording of memory for several minutes or seconds.

Let us further assume that we are treated in this way repeatedly — say, after every p seconds — every time extinguishing our memory for a short blacked out span of q seconds. (We assume p > q.)

(a) We see at once that if the periods p were made equal to the extinguished periods q, no recorded memory would be left of the whole period of the experiment.

(b) Since the periods p are somewhat longer than the periods q, there will be a sequence of recordings left, each of the length p—q.

(c) Now assume (b); and further, that p—q becomes very short. I suggest that in this case we should lose consciousness for the whole period of the experiment. For after every memory loss (even upon waking up from deep sleep) it takes some little time before we can, as it were, re-assemble ourselves and become fully conscious. If this time needed to become fully conscious (say 0.5 seconds) exceeds p—q then, I suggest, there will not be any brief moments of consciousness or awareness whose memory is extinguished; rather, there will be no moment of consciousness or awareness at all.

To put my thesis in a different way, a certain minimum span of continuity of memory is needed for consciousness or awareness to arise. Thus the atomization of memory must destroy conscious experience and, indeed, any form of conscious awareness.

Consciousness, and every kind of awareness, relates certain of its constituents to earlier constituents. Thus it cannot be conceived of as consisting of arbitrarily short events. There is no consciousness without a memory that links its constituting "acts of awareness"; and these, in their turn, cannot exist unless they are linked to many other such acts.

These results of a purely speculative thought experiment are corroborated, as far as this is possible, by some of the results of brain physiology. I am told that some drugs used as total anaesthetics — that is, for producing unconsciousness — act in the manner described, that is, as more or less radical atomizers of memory connections, and thus of awareness. Some forms of epilepsy also seem to work in a similar way. In all these cases parts of the long term memory are kept intact, in the sense that upon the recovery of consciousness the patient can remember events of his earlier life or events up to losing consciousness; and it is this past memory (or so it seems) which makes it possible for the patient to preserve his self-identity.15

Now this thought experiment speaks strongly against the theory of panpsychism according to which atoms, or elementary particles, have something like an inside view; an inside view that constitutes the unit, as it were, out of which the consciousness of animals and men is formed. For according to modern physics, atoms or elementary particles have emphatically no memory: two atoms of the same isotope are physically completely identical, whatever their past history. For example, if they are radioactive, their probability or propensity to decay is exactly the same, whatever the difference in their past radioactive history may be. But this means that they have, physically, no memory. If psycho-physical parallelism is assumed, their "inside state" must also be one without memory. But then, this cannot be anything like an inside state: it cannot be a state of consciousness, or even of consciousnesslike pre-consciousness.

Memory-like states do occur in inanimate matter; for example, in crystals. Steel "remembers" that it has been magnetized. A growing crystal "remembers" a fault in its structure. But this is something new, something emergent: atoms and elementary particles do not "remember", if present physical theory is correct.

Thus we should not assign inside states, or mental states, or conscious states to atoms: the emergence of consciousness is a problem that cannot be avoided, or mitigated, by a panpsychist theory. Panpsychism is baseless, and Leibniz's monadology must be rejected.

It might be added that it now looks as if the beginning of human or animal memory is to be found in the genetic mechanism; that memory in the conscious sense is a late product of genetic memory. The physical basis of genetic memory seems to be within the reach of science, and the explanations that we have of it seem to make it totally unrelated to any panpsychistic effect. That is to say, instead of a straight progression from memory-lacking atoms to the memory of magnetized iron, and further to the memory of plants and to conscious memory, there appears to be a huge detour via genetic memory. Thus the results of modern genetics speak strongly against the view that there is any value in panpsychism — that is, against its explanatory power or explanatory prospects, although panpsychism as such is so metaphysical (in a bad sense) and has so little content that we can hardly talk about its explanatory value.

12 1 It seems to have been influenced by Goethe's novel Elective Affinities (Die Wahlverwandtschaften = The Chosen [Chemical] Affinities) in which sympathy, and attraction, were interpreted as akin to chemical affinity. Schopenhauer, who knew Goethe personally, was greatly influenced by him.

13 For a fuller discussion of the history of the mind-body problem, see chapter P5, below.

14 (Added in proofs.) Professor Rensch has kindly informed me that he disagrees with the view stated in the first part of this sentence, since he is not a parallelist, but an identity theorist. (But in my view the identity theory is a special case - a degenerate case - of parallelism; see also sections 22 to 24, below.)

15 See especially the remarks on the patient H. M. in Brenda Milner [1966].

William Kingdon Clifford was a panpsychist. His friend, Thomas Huxley, was an epiphenomenalist. Both agreed in adopting the physicalist principle of the closedness of the physical world (World 1). In Clifford's words ([1886], p. 260): "all the evidence that we have goes to show that the physical world gets along entirely by itself. . .".

The difference between epiphenomenalism and panpsychism is mainly this.

(1) Epiphenomenalism does not assert that all material processes have a psychical aspect, and

(2) Epiphenomenalism is very far from regarding conscious states or processes as the things in themselves, as at least some of the post-Leibnizean and post-Kantian panpsychists do.

(3) Epiphenomenalism may be linked with a parallelist view (like a partial panpsychism) or it may allow for a one sided causal action of the body upon the mind. (The latter view is liable to clash with Newton's third law — the equality of action and reaction.1) I will criticize here a parallelist epiphenomenalism; but nothing in my criticism depends on this choice.

Huxley ([1898], p. 240; cp. pp. 243f.) puts his epiphenomenalism very well: "Consciousness . . . would appear to be related to the mechanism of [the] body, simply as a . . . [side] product of its working, and to be as completely without any power of modifying that working as the [sound of a] steam-whistle which accompanies the work of a locomotive ... is without influence upon its machinery."

Thomas Huxley was a Darwinian — in fact, the first of all Darwinians. But I think that his epiphenomenalism clashes with the Darwinian point of view. For from a Darwinian point of view, we are led to speculate about the survival value of mental processes. For example we might regard pain as a warning signal. More generally, Darwinists ought to regard "the mind", that is to say mental processes and dispositions for mental actions and reactions, as analogous to a bodily organ (closely linked with the brain, presumably) which has evolved under the pressure of natural selection. It functions by helping the adaptation of the organism (cp. the discussion of organic evolution in section 6, above). The Darwinian view must be this: consciousness and more generally the mental processes are to be regarded (and, if possible, to be explained) as the product of evolution by natural selection.

The Darwinian view is needed, especially, for understanding intellectual mental processes. Intelligent actions are actions adapted to foreseeable events. They are based upon foresight, upon expectation; as a rule, upon short term and long term expectation, and upon the comparison of the expected results of several possible moves and countermoves. Here preference comes in, and with it, the making of decisions, many of which have an instinctual basis. This may be the way in which emotions enter the World 2 of mental processes and experiences; and why they sometimes "become conscious", and sometimes not.

The Darwinian view also explains at least partly the first emergence of a World 3 of products of the human mind: the world of tools, of instruments, of languages, of myths, and of theories. (This much can be of course also admitted by those who are reluctant, or hesitant, to ascribe "reality" to entities such as problems and theories, and also by those who regard World 3 as a part of World 1 and/or World 2.) The existence of the cultural World 3 and of cultural evolution may draw our attention to the fact that there is a great deal of systematic coherence within both World 2 and World 3; and that this can be explained — partly — as the systematic result of selection pressures. For example, the evolution of language can be explained, it seems, only if we assume that even a primitive language can be helpful in the struggle for life, and that the emergence of language has a feedback effect: linguistic capabilities are competing; they are being selected for their biological effects; which leads to higher levels in the evolution of language.

We can summarize this in the form of the following four principles of which the first two, it seems to me, must be accepted especially by those who are inclined towards physicalism or materialism.

(1) The theory of natural selection is the only theory known at present which can explain the emergence of purposeful processes in the world and, especially, the evolution of higher forms of life.

(2) Natural selection is concerned with physical survival (with the frequency distribution of competing genes in a population). It is therefore concerned, essentially, with the explanation of World 1 effects.

(3) If natural selection is to account for the emergence of the World 2 of subjective or mental experiences, the theory must explain the manner in which the evolution of World 2 (and of World 3) systematically provides us with instruments for survival.

(4) Any explanation in terms of natural selection is partial and incomplete. For it must always assume the existence of many (and of partly unknown) competing mutations, and of a variety of (partly unknown) selection pressures.

These four principles may be briefly referred to as the Darwinian point of view. I shall try to show here that the Darwinian point of view clashes with the doctrine usually called "epiphenomenalism".

Epiphenomenalism admits the existence of mental events or experiences — that is, of a World 2 — but asserts that these mental or subjective experiences are causally ineffective byproducts of physiological processes, which alone are causally effective. In this way the epiphenomenalist can accept the physicalistic principle of the closedness of World 1, together with the existence of a World 2. Now the epiphenomenalist must insist that World 2 is indeed irrelevant; that only physical processes matter: If a man reads a book, the decisive thing is not that it influences his opinions, and provides him with information. These are all irrelevant epiphenomena. What matters is solely the change in his brain structure that affects his disposition to act. These dispositions are indeed, the epiphenomenalist will say, of the greatest importance for survival: it is only here that Darwinism comes in. The subjective experiences of reading and thinking exist, but they do not play the role we usually attribute to them. Rather, this mistaken attribution is the result of our failure to distinguish between our experiences and the crucially important impact of our reading upon the dispositional properties of the brain structure. The subjective experiential aspects of our perceptions while reading do not matter; nor do the emotional aspects. All this is fortuitous, casual rather than causal.

It is clear that this epiphenomenalist view is unsatisfactory. It admits the existence of a World 2, but denies it any biological function. It therefore cannot explain, in Darwinian terms, the evolution of World 2. And it is forced to deny what is plainly a most important fact - the tremendous impact of this evolution (and of the evolution of World 3) upon World 1.

I think that this argument is decisive.

To put the matter in biological terms, there are several closely related systems of controls in higher organisms: the immune system, the endocrinal system, the central nervous system, and what we may call the "mental system". There is little doubt that the last two of these are closely linked. But so are the others, if perhaps less closely. The mental system has, clearly, its evolutionary and functional history, and its functions have increased with the evolution from lower to higher organisms. It thus has to be linked with the Darwinian point of view. But epiphenomenalism cannot do this.

An important but separate criticism is this. If applied to arguments, and our weighing of reasons, the epiphenomenalist view is suicidal. For the epiphenomenalist is committed to arguing that arguments or reasons do not really matter. They cannot really influence our dispositions to act — for example, to speak or to write — nor the actions themselves. These are all due to mechanical, physico-chemical, acoustical, optical and electrical effects.

Thus the epiphenomenalist argument leads to the recognition of its own irrelevance. This does not refute epiphenomenalism. It merely means that if epiphenomenalism is true, we cannot take seriously as a reason or argument whatever is said in its support.

The problem of the validity of this argument was raised by, among others, J. B. S. Haldane. It will be discussed in the next section.

1 The principle is re-affirmed by Einstein ([1922]; [1956], chapter 3, p. 54) when he says: ". . . it is contrary to the mode of thinking in science to conceive of a thing. . . which acts itself, but which cannot be acted upon."

The argument against materialism mentioned at the end of the previous section was concisely formulated by J. B. S. Haldane. Haldane [1932] puts it thus: ". . . if materialism us true, it seems to me that we cannot know that it is true. If my opinions are the result of the chemical processes going on in my brain, they are determined by the laws of chemistry, not of logic."16

The argument (retracted by Haldane in a paper "I Repent an Error" [1954]17) has a long history. It can be traced back at least to Epicurus: "He who says that all things happen of necessity cannot criticize another who says that not all things happen of necessity. For he has to admit that the assertion also happens of necessity."18 In this form, it was an argument against determinism rather than against materialism. But the close relationship between the arguments of Haldane and Epicurus is striking. Both indicate that if our opinions are the result of something other than the free judgement of reason,19 or the weighing of reasons, of the pros and cons, then our opinions are not worth taking seriously. Thus an argument that leads to the conclusion that our opinions are not arrived at in this way defeats itself.

Haldane's argument (or more precisely, the second of the two sentences quoted above) cannot be upheld in the form here stated. For a computing machine may be said to be determined in its working by the laws of physics; but it may nevertheless work in full accordance with the laws of logic. This simple fact invalidates (as I pointed out in section 85 of my unpublished Postscript) the second sentence of Haldane's argument as it stands.

However, I believe that Haldane's argument (as I will call it in spite of its antiquity) can be so revised as to become unexceptionable. Although it does not show that materialism destroys itself, I suggest that it shows that materialism is self-defeating: it cannot seriously claim to be supported by rational argument. The revised argument of Haldane could be put more concisely, but I think it is clearer if developed at length.

I will represent the revised argument in the form of a dialogue between an interactionist and a physicalist.

Interactionist I am quite prepared to accept your refutation of Haldane's argument: the computer constitutes a counter-example to this argument as it stands. However, it seems to me important to remember that the computer, which admittedly works on physical principles and at the same time also according to logical principles, has been designed by us — by human minds — to work like this. In fact, a great amount of logical and mathematical theory is being used in the making of computers. This explains why it works according to the laws of logic. It is far from easy to construct a piece of physical apparatus that works according to the laws of physics and, at the same time, according to the laws of logic. Both the computer and the laws of logic belong emphatically to what is here called World 3.

Physicalist I agree, although I admit only the existence of a physical World 3 to which, for example, books on logic and mathematics belong, and, of course, also computers: this World 3 of yours is in fact part of World 1. Books and computers are products of men and women — they are designed; they are products of human brains. Our brains in turn are not really designed — they are largely the products of natural selection. They are so selected as to adapt themselves to their environment; and their dispositional capacities for reasoning are the result of this adaptation. Reasoning consists in a certain kind of verbal behaviour and in acquiring dispositions to act and to speak. Apart from natural selection, positive and negative conditioning through the success and failure of our actions and reactions also play their role. So does schooling; that is to say, conditioning through a teacher who works upon us — somewhat like a designer who works on a computer. In this way we become conditioned to speak and to act and to reason rationally or intelligently.

Interactionist It seems that you and I agree on a number of points. We agree that natural selection and individual learning play their role in the evolution of logical thinking. And we agree that a reasonable or a reasoning materialism is bound to assert that a well trained brain, like a reliable computer, is built in such a way that it works in accordance with the principles of logic and with those of physics and electro-chemistry.

Physicalist Precisely. I am even prepared to admit that if this view cannot be upheld, then Haldane's argument would actually upset materialism: I would have to admit that materialism undermines its own rationality.

Interactionist Do computers or brains never make mistakes?

Physicalist Of course computers are not perfect. Nor are human brains. This goes without saying.

Interactionist But if so, you need World 3 objects, such as standards of validity, which are not embodied or incarnated in World 1 objects: you need them to be able to appeal to the validity of an inference; yet you deny the existence of such objects.

Physicalist I do deny the existence of non-corporeal World 3 objects; but I do not quite see your point yet.

Interactionist My point is quite simple. If computers or brains may fail, what do they fall short of?

Physicalist Of other computers or brains or of the contents of books on logic and mathematics.

Interactionist Are these books infallible?

Physicalist Of course not. But mistakes are rare.

Interactionist I doubt that, but let it be so. I still ask: if there is a mistake — mind you, a logical mistake — by what standard is it a mistake? Physicalist By the standards of logic.

Interactionist I fully agree. But these are abstract non-corporeal World 3 standards.

Physicalist I do not agree. They are not abstract standards, but the standards or principles which the great majority of logicians — in fact, all except a lunatic fringe — are disposed to accept as such.

Interactionist Are they so disposed because the principles are valid, or are the principles valid because logicians are disposed to accept them? Physicalist A tricky question. The obvious answer to it, and at any rate your answer, would seem to be "logicians are disposed to accept logical standards because these standards are valid". But this would admit the existence of non-corporeal and thus of abstract standards or principles whose existence I deny. No, I have to give a different reply to your question: the standards exist, so far as they exist, as states or dispositions of the brains of people: states, or dispositions, which make people accept the proper standards. You may now, of course, ask me "What else are the proper standards but the valid standards?" My answer is "certain ways of verbal behaviour, or of connecting some beliefs with others; ways which have proved useful in the struggle for life, and which therefore have been selected by natural selection, or learned by conditioning, perhaps in school, or otherwise".

These inherited or learned dispositions are what some people would call "our logical intuitions". I admit that they exist (as opposed to abstract World 3 objects). I also admit that they are not always reliable: logical errors exist. But these mistaken inferences may be criticized, and eliminated.20

Interactionist I do not think that we have made much progress. I have long admitted the role of natural selection and of learning (which I, incidentally, should certainly not describe as "conditioning"; but never mind the terminology). I also would insist, as you seem to do now, on the importance of the fact that we often approach truth by way of the elimination and correction of error; and like yourself, I am inclined to say that the same holds with mistaken inferences as opposed to valid inferences: we learn of an inference, or a certain way of drawing inferences, that it is invalid if we find a counterexample; that is to say, an inference of the same logical form, with true premises and a false conclusion. In other words: an inference is valid if and only if no counter-example to this inference exists. But this statement (which I have emphasized) is a characteristic example of a World 3 principle. And although the emergence of World 3 can be, partly, explained by natural selection, that is to say, by its usefulness, the principles of valid inference, and their applications, which belong to World 3, cannot all be explained in this way. They are partly the unintended autonomous results of the making of World 3.

Physicalist But I stick to my point that only the physiological dispositions (more precisely, dispositional states21) exist. Why should not dispositions evolve or develop which I may describe as dispositions to act in accordance with a routine? For example in accordance with what you call the logical standards of truth and validity? The main point is that the dispositions are useful in the struggle for survival.

Interactionist That may sound all right, but it seems to me to avoid the real issue. For dispositions must be dispositions to do something. If we ask what this something is, you seem to indicate that your answer would be "to act in accordance with a routine". But can we not then ask "What routine?" — and this, I think, would lead us back to World 3 principles.

But let us look at the matter from another angle. The property of a brain mechanism or a computer mechanism which makes it work according to the standards of logic is not a purely physical property, although I am very ready to admit that it is in some sense connected with, or based upon, physical properties. For two computers may physically differ as much as you like, yet they may both operate according to the same standards of logic. And vice versa; they may differ physically as little as you may specify, yet this difference may be so amplified that the one may operate according to the standards of logic, but not the other. This seems to show that the standards of logic are not physical properties. (The same holds, incidentally, for practically all relevant properties of a computer qua computer.) Yet they are, according to you and me, useful for survival.

Physicalist But you say yourself that the property of a computer which makes it work according to the standards of logic is based upon physical properties. I do not see why you deny that this property is a physical property. Surely, it can be defined in purely physical terms. We simply build a logical computer, which is a physical object. Then we define the relations between its input and its output as the standards of logic. In this way we have defined a standard of logic in purely physical terms.

Interactionist No. Your computer may break down. This may happen to any computer. Incidentally, you could just as well choose as your standard a particular copy of a logical text book. However, it may have mistakes in it, either printing mistakes or others. No, standards belong to World 3, but they are useful for survival; which means that they have causal effects in the physical world, in World 1. Thus the abstract World 3 property of a computer which we can describe by saying "its operations conform to logical standards" has physical effects: it is "real" (in the sense of section 4 above). This causal action upon World 1 is precisely the reason why I call World 3, including its abstract objects, "real". If you admit that conformity with logical standards is useful for survival, you admit the usefulness of logical standards, and so their reality. If you deny their reality, why is the similarity between useful computers and the difference between a useful computer and a useless one not to be found in their physical similarity or dissimilarity but in their ability or disability to work in accordance with logical standards?

Physicalist I am still unconvinced. Is usefulness for survival purposes according to you a property belonging to World 1, as I think, or do you count it as belonging to World 3?

Interactionist It depends. The usefulness of a natural organ I am inclined to count as a property belonging to World 1 objects, while that of man-made tools may be a property belonging to World 3 objects.

Physicalist But the brain, and its states and processes, are World 1 objects; and so are verbal expressions such as statements or theories. Could we not simply accept a suggestion of William James's and call a theory true if it is useful? And could we not similarly call an inference valid if it is useful?

Interactionist You can, of course, but you do not gain anything. Admittedly, truth is useful in many contexts; it is so especially if one adopts the World 3 aims and purposes of a scientist, a theoretician; that is, to explain things. From this point of view, valid inference is particularly valuable or "useful", because we can look at explanation as a certain kind of (usually abbreviated) valid inference. But although we can say that in this sense truth is useful, it leads to great trouble if we try (with William James) to identify truth and usefulness.

Physicalist How does it lead to trouble?

Interactionist If one thinks of a true theory as useful, then one does so mainly because of the usefulness of its true informative content. But a theory may be true even if its informative content is negligible, or nil: a tautology like "All tables are tables" or perhaps "1 = 1" is true; but it has no useful informative content. This has its repercussions on the usefulness of validity.

A valid inference always transmits truth from the premises to the conclusion and retransmits falsity from the conclusion to at least one of the premises. Is this perhaps enough to show its instrumental value? It is not, for the premises may be true and useful but the conclusion may be true and useless, as I have just shown. The point is that the informative content of a validly derived conclusion can never exceed that of the premises. (If it does a counterexample can be found.) But the informative content can deteriorate in a valid inference. In fact, it may be zero. For example, a valid conclusion drawn from some highly informative and useful theory may be just a tautology like "1 = 1", which is not informative and therefore no longer useful.

Thus a valid inference always transmits truth, but not always usefulness. It cannot therefore be shown that every valid inference is a useful instrument, or that the routine of drawing valid inferences is as such always useful.

You might wonder why you as a physicalist could not say that it is not so much every particular valid inference that is useful but the whole system of valid inferences; that is to say, logic as such. Now, it is indeed true enough that it is the system — logic — which is useful. But the problem for the physicalist is that it is just this that he cannot admit; for the point at issue between him and the interactionist is precisely whether such things as logic (which is an abstract system) exist (over and above particular ways of linguistic behaviour). The interactionist here takes the commonsensical view that valid inference is useful — and this, indeed, is one of the reasons why he admits its reality. The physicalist is prevented from accepting this position.

So far the dialogue. In it I have tried in brief to state some of the reasons why a materialist theory of logic and with it of World 3 does not work.

Logic, the theory of valid inference, is indeed a valuable instrument; but this cannot be made clear by an instrumentalist interpretation of valid inference Nor can, I think, such ideas as that of the informative content of a theory (an idea that depends on that of deducibility or valid inference) be made clear as long as we do not transcend the materialist point of view — the point of view that admits only the physical aspects of World 3.

I do not claim that I have refuted materialism. But I think that I have shown that materialism has no right to claim that it can be supported by rational argument — argument that is rational by logical principles. Materialism may be true, but it is incompatible with rationalism, with the acceptance of the standards of critical argument; for these standards appear from the materialist point of view as an illusion, or at least as an ideology.

I think that the argument of this section concerning validity can be generalized.

Some people assert7 that all argument is ideological and that science is just another ideology. This is clearly a self-defeating relativism. It is sometimes connected with the thesis that there is no such thing as a pure standard of validity, or a pure theory, but that all knowledge works in the interest of human interests — such as socialism and capitalism. Reply: are computers in a socialist Utopia to be constructed differently from those in a capitalist society? (Of course, they may be differently programmed; but this is trivial, as they will always be differently programmed if used to solve different problems.)

16 See J. B. S. Haldane [1932], reprinted in Penguin Books (| 1937], p. 157); see also Haldane

17 [1930], p. 209.

18 2 J. B. S. Haldane [1954], See also Antony Flew [1955]. A more recent rejection of what I call Haldane's argument, due to Keith Campbell, can be found in Paul Edwards, ed. [1967 (b)) vol.5, p. 186. See also J.J.C. Smart [1963], pp. 126f. (and Antony Flew [1965], pp. 114-15) where further references will be found, and section 85 of my (unpublished) Postscript.